Editor’s Note: Earlier this summer, Wet Ink was invited to participate in The Boccaccio Project, a beautiful initiative by The Library of Congress designed to keep composers and performers employed and making art during the pandemic. On their Website, The Library of Congress writes, “In the mid-14th century Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) wrote the Decameron, a collection of 100 stories shared between a group of 10 acquaintances who had removed themselves from society during the darkest period of a plague. This early artistic response to an outbreak provided context and a means of expression, and the parallels to the quarantine and social distancing phenomena we have been experiencing worldwide in these difficult past few months resonate with us.” The Library of Congress commissioned ten works, including two by Wet Ink collaborators Erin Rogers and Ashkan Behzadi, to be written over a short period and premiered online in June by Wet Ink members Erin Lesser and Mariel Roberts. For Archive 03, these four innovative artists share their reflections on the process behind the new works.

HELLO WORLD

————Erin Rogers

[Composer]

The best part about a short timeline is there’s barely time to think. I like a quick decision. I’ll take a solid trial-and-error system over days of rumination. That’s not a rule, but I’ve noticed the freshness of channeling a first instinct, and the value of moving on it when time is currency, not to mention the risk of paralysis given an abundance of theoretical space. We had a period of about four weeks – two weeks to compose a solo flute piece and two weeks to learn/perform/record it. I had heard Erin Lesser perform with Wet Ink and Alarm Will Sound but you don’t really know what to expect until you get into a room together (a Zoom room in this case). ErinL was helpful and patient as I badly demonstrated on my broken, borrowed flute, a few sounds and ideas that were simmering. Having been on both sides of this moment, it can go either way. There’s a performer anxiety when asked to achieve unrefined sounds made by untrained players. There’s a rightful skepticism to being asked to hold your instrument in an unfamiliar way. There’s a nervousness about notation, especially in a time crunch and especially with someone you’ve just met. The way to mitigate this zone is to get on (and over) it immediately. ErinL reached out the same day the project got the green light. We set up a meeting and she offered a strong schedule for the next few weeks. In addition to an overwhelming receptiveness to my ideas, she learned and executed everything. She worked on the choreography until it was solid. She set up a green screen, figured out the mic/reverb/pedal situation, loaded up the weird video software and performed the work with a focus and energy that could only occur through complete internalization of the score. So she memorized it. Total dedication. Our video was completed with time to spare. David Plylar from the Library of Congress was equally organized, forthcoming with project details, and welcomed the electronics and video effects. “This is how every project should work,” I thought. “I wonder if it went like this for Mr. Boccaccio?”

Erin Rogers: Hello World, performed by Erin Lesser (flute)

The program note for Hello World reads something like: Orbiting a sonic portal to the outerworld, a flutist self-arranges within a mirrored video frame. The face-to-face encounter sets the scene for introduction, reintroduction, and exploration.

Perhaps it’s better described like this:

“I just figured out a new language. What should I say?”

“Welcome to your first virtual job interview. What is your name?”

“Hi world. Did you forget about me?”

“It’s been over a month of isolation. Can I please leave my house?”

“I’m trapped in the internet.”

Or the autobiographical:“Is my best side the left or the right?”

Erin Lesser stands in front of a green screen, logged into a personal zoom meeting, running a free video software program called Camtwist to achieve the digital, two-tone effect. She exists somewhere. Her eyes move between human and machine as light and sound change. The opportunity to expand forces are always welcome, especially in a solo work. The choice to renovate the play space came with the addition of choreography, video software, voice/text effects and a reverb pedal. These tools could help create a musical frame narrative, a multi-layered work, a story within a story, not unlike The Decameron.

Embracing the recorded aspect of the project came by selecting the mic as the central point of focus. Orbiting the mic proved fruitful. It provided a starting point to the narrative form and allowed proximity to become an element of visual play in addition to sound alteration. This provided a built-in “why” for the choreography while at the same time bolstering the energy of the scene by creating vectors that aligned directly with sonic results. Building expectation, for example a quick movement toward the mic, can elicit a strong reaction as not only does volume increase, but by mapping volume to a visual action the gesture fulfills an expectation. After three crescendo gestures toward the mic, the same motion again, but with no sound, will elicit the same reaction as the three prior times, but with a twist – on the fourth iteration, the sound exists purely in an imagined state. Before the listener can acknowledge this absence-of-sound, a composer takes advantage of the moment by applying a different sonic texture to the end of the silent gesture, aka “the old bait and switch”. If this is an example of a visual dynamic, then there is also an element of visual counterpoint that comes and goes. By prescribing a speed at which body movements occur, a second rhythmic layer, this one visual, is applied to the existing line. For example, a visual gesture set between two played eighth notes that must itself take place within the span of an eighth note, creates a rhythmic continuity of three successive eighth notes rather than two eighths with an eighth rest between them. The visual substitution for this negative space (the eighth rest) provides an intentional rhythmic use of this resting space while allowing for the sonic break and a split second of aural reprieve and reflection. Inversely but equally effective, a long, drawn-out body shift can act as a visual drone, providing a bed for other sonic elements to layer over.

The text “Hello, my name is Erin” is translated into three languages, emerging through whispers, phonetic attacks, glitched syllables, sung syllables, spoken words, and full phrases. Text functions mainly as a musical device however traces of intelligibility accumulate and may even provide a meaningful takeaway. In other words, if you did not know the name of the performer while listening to this work, by the end your first guess might be “Erin.” The venting of whispered and spoken words through keyholes obscures the text and alters quality, creating a robotic voice, while following the syllable “s” through a gradual closure of key holes down the body of the flute creates a panning effect of audible air. Add a left-shifting body motion to the panning and you double the impact.

In a more literal attempt to raise the ceiling, the addition of a reverb pedal put space dimension into play. Wet/dry became large/small and could contribute to the existing narrative. The room could now expand and contract on command and the listener, not sharing the same physical space, could be convinced that the performer had transported. Upon hearing a sudden long decay, one might imagine a wall had opened behind the camera revealing a vast cavern or that ErinL had somehow entered a portal to another world, furthering the “trapped in the internet” scenario. Perhaps she traveled back in time to 1352 to scoop a first edition copy of Boccaccio’s seminal work? By now the piece had reached the 3-minute limit.

Erin Lesser

[Flutist]

I played my final concert of 2019 at the beginning of November. At eight months pregnant, it was time to stop travelling and start nesting. I started the year with maternity leave and a newborn baby and the longest hiatus from playing and performing that I’ve had in years. By March, I was excited to get back to teaching, see my colleagues and friends and resume creative projects. Instead, students returned home, lessons went online and performances were postponed and then cancelled. When the invitation came to participate in the Boccaccio Project, my exhaustion was replaced by the allure of a creative project. With a quick deadline came meetings to discuss techniques and notation, late-night sessions choreographing movements in Zoom and a welcome injection of motivation and energy.

In our first meeting, ErinR said she was thinking about musicians trapped in small spaces, being vigilant about not making too much noise with neighbours home all the time. The piece ended up being very centered around my relationship to the microphone, and the biggest challenge for me was the theatricality that was woven into the movements, positions and timing.

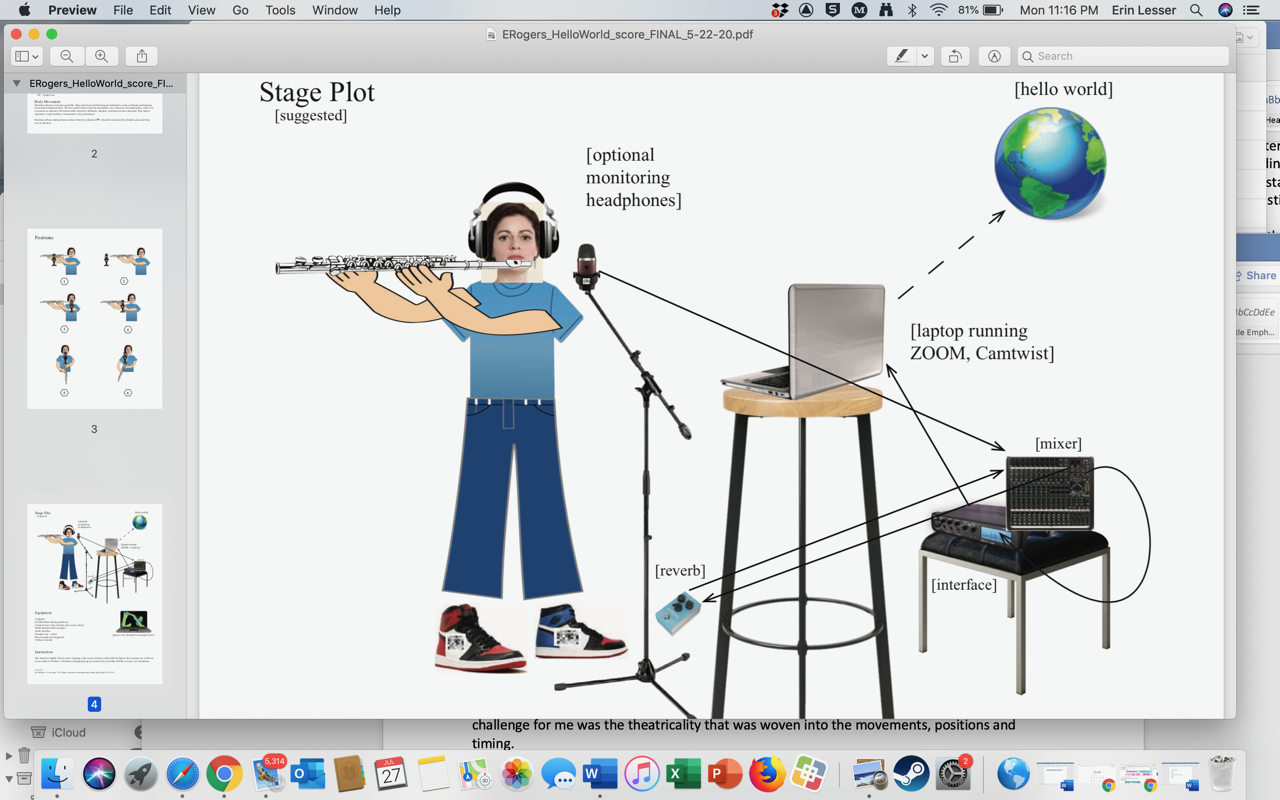

I was given six positions that each had a relationship to the microphone and captured different elements of my sound. ErinR also asked me to use a reverb pedal, and to work with a video filter that changed my image’s color and texture as I moved. I was watching myself and recording in real time on Zoom, which meant that the computer was in front of me instead of a music stand. I had to get used to moving in relation to the microphone, try to look slightly robotic, and still be able to use the reverb pedal. After many comedic mishaps, I decided that I needed to memorize the piece so that my focus could be on all of the logistical and visual aspects of the performance. My five-month old was treated to constant practice of the spoken sounds as I carried him around.

After seeing the premiere, the best feedback I received was “I can’t tell you why, but that performance summed up everything I’ve been feeling for the last three months.” I think that ErinR was able to capture our discomfort with the newness of this situation and play with the distortion of our words, images and body language as we communicate through technology. Many of us have a love/hate relationship with Zoom: it enables us to connect and continue working, but it also inhibits our ability to contextualize what we see and thus isolates us further.

The piece is disconcerting yet captivating; eerie but earnest in its desire to communicate with the audience on the other side of the screen. With its innovative use of Zoom recording as part of the performance, I think it is truly reflective of this new world we’re inhabiting and learning to navigate.

LOBELIA

————Ashkan Behzadi

[Composer]

Ashkan Behzadi: Lobelia, performed by Mariel Roberts (cello)

The physical and social aspects of the concert hall (as opposed to, say, a recording studio) have been guiding forces behind the compositional process of many of my works. By “physical aspects”, I mean the acoustics of the space and the spatialization of sound, both around the concert hall and between the musicians on the stage. By “social aspects”, I mean the alienated relationship between the musicians and the audience. More specifically:

the gap, both physical and metaphorical, between the musicians and the audience

the loneliness of the audience listening to the music in their isolated islands (their seats)

the gaze of the audience on the musicians’ labor, and

the tension between our collective memory of music as a social act and the reflective mode of listening in the setting of a concert hall.

Sometimes these notions emerge as a concept, and sometimes this concept merges into the musical material of the piece. For example, in my piece Carnivalesque, for seven musicians, I aimed to recreate the pastiche sonic experience of an imaginary carnival, as if standing in the middle of a chaotic collective celebration. The tension between our collective memory of the social space of a carnival and its contradiction with the loneliness of listening to the piece in the concert setting is the main force of the composition. Five Sketches for String Quartet deals with this idea more explicitly. The physical space between the musicians themselves becomes the force of the composition; therefore, the spatialization of the sound in the physical space, created by the half-circle formation of the string quartet, becomes a material of composition.

However, since the completion of Love, Crystal and Stone, a song cycle based on a collection of poems by Federico García Lorca, I have been preoccupied with yet another notion similarly related to the setting of a concert hall. While working on the song cycle, a thought that constantly engulfed me was the process of the creation of lyric poetry. The poet, in this case, Lorca, writes the poem as if he is reading the text to himself while sketching and reaching the final form. I was also interested in how lyric poetry is performed for audiences as if being read to oneself. Even when lyric poetry is read to us by someone else, it is always as if we are overhearing the poet reading the poem in private. This is remarkably different from the performance practice of music. The notion of “singing to yourself” in music, derived from the notion of “reading to yourself” in lyric poetry (a concept used by many literary critics, including T.S. Eliot and Northrop Frye, to distinguish lyric poetry from epic or drama), has become an important aspect of my recent compositions.

Looking beyond the concert hall, there are many musics that carry the expressive aspect of “singing to oneself” in their forms or in their material – deeply introverted music that is sung by someone simply to overcome boredom, loneliness, fear, sadness, etc. A worker singing to himself wiping the floor, a tired mother singing to herself while cooking, or a little girl whispering half of a song in a loop while jumping up and down in a park. I recently came across a documentary on the singing of carpet workers in Iran. The workers sing two kinds of songs. One has the function of coordinating the work, and is called “pattern singing”. The other are old folk songs that are sung by the workers to soothe the brutal boredom and heavy workload of making a carpet.

Excerpt from The Woven Sounds, a documentary by Mehdi Aminian

Moreover, there are cultures wherein music is not primarily created to be heard in a concert setting. For example, in traditional Iranian music, the instruments are not designed to project sound to a large audience. Rather, the instrument has a delicate design to be heard only by the performer himself.

Jalal Zolfonoon performing traditional Iranian music

When I was approached by Wet Ink ensemble to participate in the Boccaccio project to compose a new piece for the brilliant cellist Mariel Roberts, once again I returned to the notion of “singing to yourself” as the primary force behind the piece, which seemed more relevant than ever given our current isolated situation. Therefore, I thought of certain formal aspects that one singing to herself might have: a small range of register, a vague contour or fragmented melody, a small range of dynamic with momentary exponential crescendos out of the texture, a whispering quality, or momentary textural scratches. The setting was not a concert setting, but a video to be played for the public online. As if we are gazing through a window at a performer “practicing to herself” or “performing to herself” in her seclusion, the piece is imbued with the character of someone singing to herself in a moment of introverted expressivity.

Mariel Roberts

[Cellist]

I was so thrilled when I heard that the Library of Congress had selected Ashkan and me to work on a project together. I've been a huge admirer of Ashkan's music for years and had always hoped that we might find an opportunity to work on something more intensely together. The time in which this project was meant to happen was between two and a half and three months into quarantine, at which point the momentum of trying to keep up a routine, hoping for things to get better soon, and my general desire to make music were at an all-time low. Some artists have admirably kept up their drive to work and create within the bubble that the COVID quarantine created, but for me it was incredibly difficult and emotionally exhausting to stay inspired about what felt like making music in a vacuum. Then just as we were about to begin the workshop process, George Floyd was murdered and Black Lives Matter protests began raging all across the country. Instead of practicing I was going to marches and drowning in the news and questioning whether my silence would be more valuable than forcing myself to perform during these critical times. As Ashkan put perfectly in an email, I think we were both “engulfed by rage and anxiety” at the horror and brutality that was all around us, and struggling to move forward.

The first time I opened my cello case to work on Lobelia felt heart-wrenching. I had become really disconnected from my instrument and the process of working on music. The night before I'd stayed up on my roof watching swirling search helicopters and swarms of police streaming through the streets because two cops had just been killed on my block following a tense day of protests. Beginning to work was painful. It was painful because my usual deep mental and physical connection to my instrument felt like it had been dissolved by the chaos of the days and months before. But the nature of Lobelia is that it's meant to be a deeply personal and private piece - “singing to yourself” as Ashkan told me. Working on the piece felt extremely personal indeed. Rather than feeling like I was constrained by the score, it felt more like a map to help guide me on my own individual journey through the material. It was ultimately a cathartic experience to work with Ashkan on the Boccaccio Project; the connection of working with someone on music and coming out of my head and back to my instrument created a much needed safe creative space in very uncertain times.