Editor’s Note: Smoke, Airs (Huddersfield Contemporary Records 24), an album which represents the culmination of several years of collaboration between Huddersfield, UK-based composers and Wet Ink, comes out on September 25th. We are lucky that the brilliant flutist/vocalist Alice Teyssier was available to join us for this project, from performances of these four new works at the 2019 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (hcmf//), to the US premieres at St. Peter’s Chelsea in NYC and the studio recordings. Below, Alice shares her reflections on the project intertwined with words from the composers. The article is accompanied by documentation from the NYC performance.

Bzz. Bzz. Bzz, Bzz. Seventy-two buzzes per minute. Pumps per minute. I look down at the bottles, filling up faster than they ever have. I look at my phone: three minutes until recording starts. Better wrap this up, go wash up.

Time - its value, your perception of it, to whom it “belongs”, the before, the after - changes when you have a child. A baby requires your complete availability, regardless of the hour, regardless of how much they have already taken. There are no boundaries to the contract you make with your child. In some ways, it resembles musical performance at its best: you lose your sense of any outside forces, and your entire being is given over to being IN that moment. Time, heretofore a relatively objective parameter, takes on a mysterious multiplicity, a multiplicitous mystery.

I was overjoyed when Josh Modney asked me to join Wet Ink for their residency at the 2019 Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival (hcmf//), especially because I would be standing in for Erin Lesser, who was herself preparing for the arrival of her child. At the time of the festival, my own son Lucien was almost one year old, and I had not yet left him overnight. I packed my pump alongside all my flutes, along with a large cooler bag with as many ice packs as I could find on the local “buy nothing” group. I would be gone four nights, a quick trip by any other measure for me, a seasoned traveling musician, and yet this would end up feeling like the longest trip of my life.

As always, the music proved to be a point of reflection and reverberation with my fascination - and battle, sometimes - with time, with each composer treating some element of time in their own unique ways. In thinking, remembering and writing about these works now, it is remarkable to me how much is etched in the body before it comes to the mind; it is time, slowly, deliberately, which reveals layer upon layer of our lived experience, transforming practice into understanding.

Wet Ink had an incredibly full plate at hcmf//, putting on two discrete concerts on consecutive days, while also making a record, Smoke, Airs, which comes out this week on Huddersfield Contemporary Records. I did manage to enjoy at least one meal of fish & chips and a good deal of excellent beer, and make friends with the hotel restaurant staff, who kindly stashed my breastmilk in their freezer. For this issue of Wet Ink Archive, I spoke with the composers featured on this newest release - Bryn Harrison, Kristina Wolfe, Pierre Alexandre Tremblay, and Charmaine Lee - about their pieces and their experience working with Wet Ink. It is my honor to have contributed to the performances and recordings of these works, and to have continued to think deeply about them through writing this entry.

BRYN HARRISON: DEAD TIME

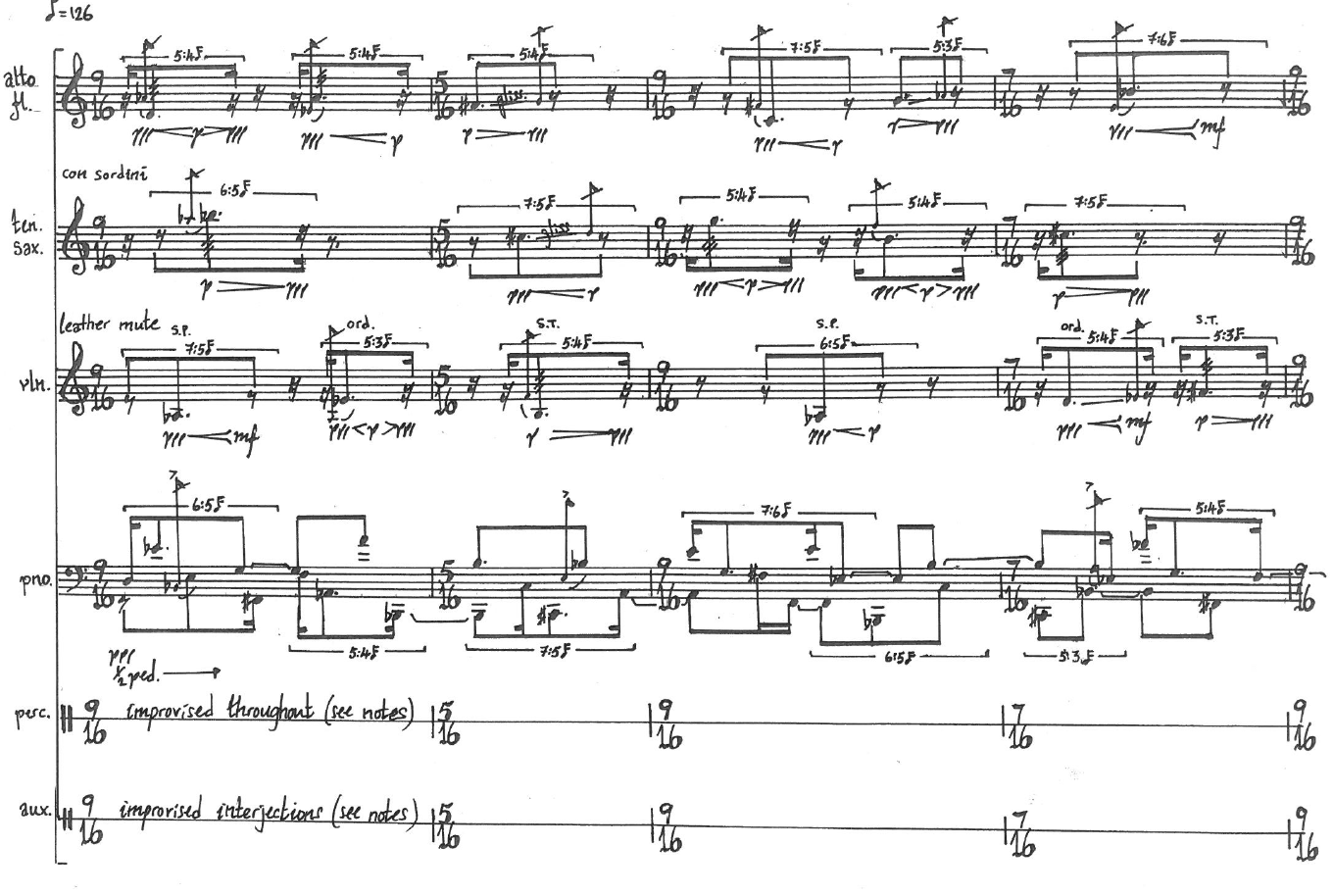

When we convened in September of 2019 for preliminary rehearsals, we were confronted with thirty-seven pages of score from Bryn Harrison that looked like this:

After a few panicked minutes, we looked to Josh Modney, scroll conductor extraordinaire, to see if we could accomplish the piece with precision and confidence; as usual, he saved the day and managed not only his highly complex part, but also a gestural performance of the meter.

The work lives in a quiet, intimate sound world, bubbling along with very slight variations and high degrees of repetition over prolonged periods of time. The performers must remain highly vigilant in the local aspect of time, while the listener has the duration of the piece unfold before them. Maintaining focus and concentration while performing at a low dynamic level and achieving synchronicity between parts is especially difficult, and exhausting, particularly through the long repetitions at the end. Four of the instrumental parts (alto flute, tenor saxophone, violin and piano) are notated precisely, with lots of tricky, tuplet rhythms, while the percussion and electronic parts are written more freely, allowing scope for improvisation and spontaneity.

In my correspondence with Bryn, he wrote “In a way, the piece is very much about exploring perceptual thresholds and the sense of redundancy that occurs when things cease to change. I was constantly asking myself, what happens if the repetitions go on for too long and become boring or challenging to listen to? What are the structural implications and what happens when we come out of one of these loops?”

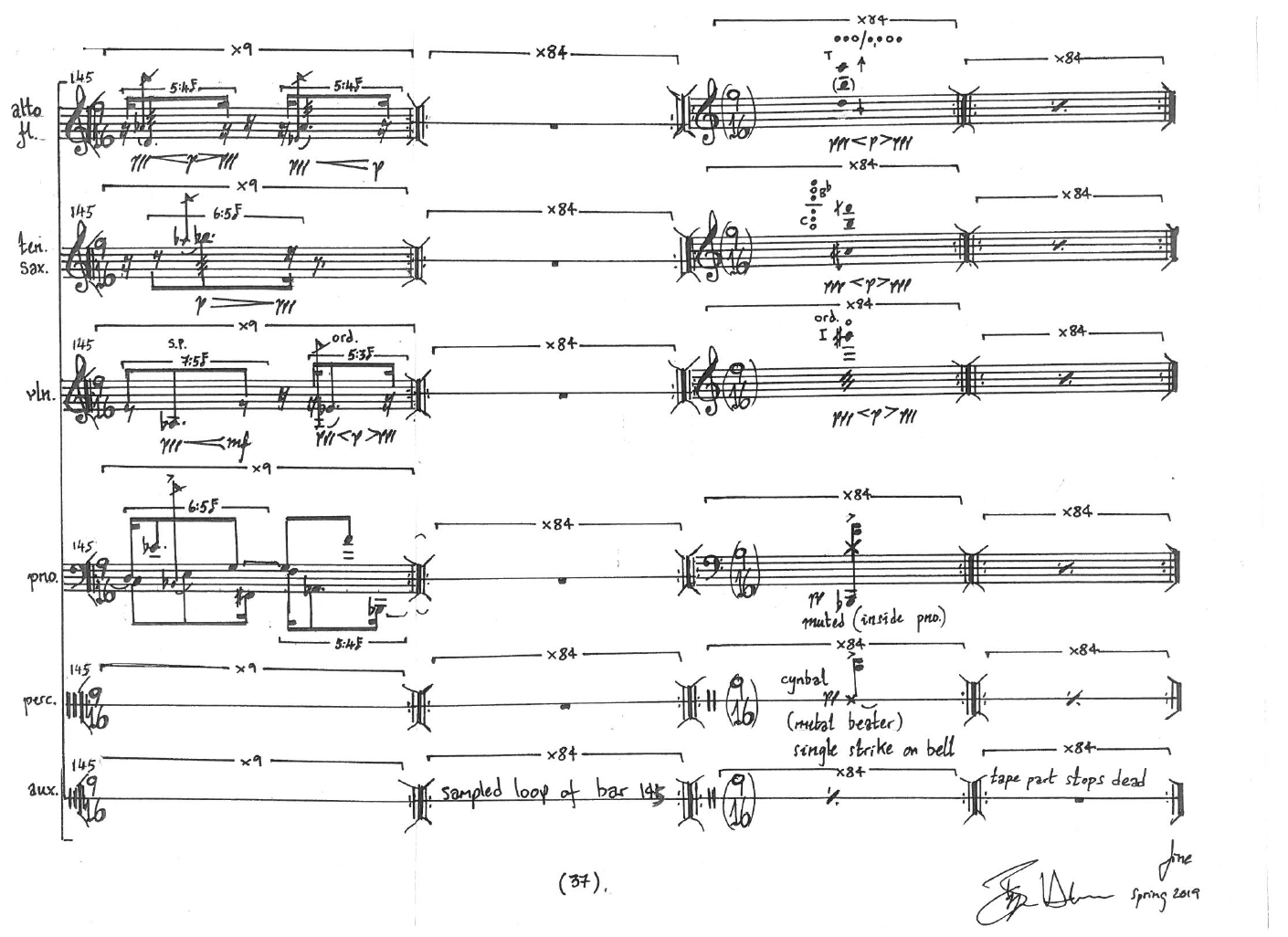

Dead Time plays with human fallibility and sonic illusions using a “digitized" version of time. The last few minutes of the piece involve extreme quantities of repetitions of small sonic envelopes, oscillating between the fragility of humans attempting mechanical repetition, followed by a repeated digital snapshot of the same loop:

Bryn spoke to me of the “fundamental differences between a digitized loop (a loop that is generated through the process of sampling) and a performative loop (a loop that is created by musicians through the act of repeating a musical gesture as precisely as possible).” He elaborates:

Performed loops, I would argue, are always in a state of becoming as there are always noticeable differences in the body language of the performers and an awareness that each repetition comes from the conscious attempt to perform the previous action again (rather than mechanically repeating the same action). Digitized loops, on the other hand, always reproduce the same encoded information in the same way. There are nonetheless some perceptual similarities since the playback of a digitized loop still takes place, for the listener, in real time. This means that some aspect of change must still be taking place, even if - as the philosopher David Hume would have us believe - this occurs more directly within the mind that perceives it. The piece intentionally plays with both types of loop, testing perceptual thresholds, boundaries, and states of ambiguity.

As for the title, Dead Time refers to those liminal states in which movement may appear (perhaps only momentarily) to have ceased entirely. Bryn shared with me the inspiration, from Lisa Baraitser’s book Enduring Time:

I am seeking…lived experiences of time that appear neither eventful nor vital, and whose ‘multiplicity’ is overwhelmed by their singularity – the obdurate situation of poverty that does not change, of incarceration with no end, of the dead that will not return, of the slow circularity of time on the psychoanalytical couch… I am drawn to temporal tropes that are linked together by an apparent lack of dynamism or movement: waiting, staying, delaying, enduring, persisting, repeating, maintaining, preserving and remaining. (Baraitser, 2017)

“The piece [Dead Time] was written prior to the recent pandemic but I can’t help thinking that the title now appears rather morbid. It is a fitting example though of how things become inevitably recontextualised through time!”

KRISTINA WOLFE: A MERE ECHO OF ARISTOXENUS

Kristina Wolfe’s A Mere Echo of Aristoxenus is scored in two movements, for different instrumentations; the first movement is entitled “Ghost Aulos for Vetruvius” and the second “Heptaechon”. We are transported back to the Romans and the Greeks, and their conceptions of acoustics and sound. Kristina calls the foundation of the work “a translation of a translation of an idea colored by a modern ear, a highly distorted echo of an original concept” - a palimpsest of meaning, a reconstruction of possibility.

“Ghost Aulos for Vitruvius” (scored for electronics, bass flute, tenor saxophone, and violin, with intermittent hits from the piano and vibraphone) reimagines two different sounding events. The first are “sounding vessels”, described by Vetruvius in his De Architectura, within a virtual amphitheatre. These sounding vessels, the mere existence of which is rather contentious among historians, were supposedly used to enhance the voices of performers and augment the acoustics of the amphitheater. In the piece, Sam Pluta plays the sounding vessels and the virtual space as electronic instruments. The second reconstruction is of the timbre of the ancient Greek reed instrument, the aulos. The bass flute, tenor sax, and violin merge timbres to create a type of ‘ghost’ aulos. The piano remains sparse because of its powerful effect on the resonating bodies in the electronics. The vibraphone, itself a “shape-shifting sounding vessel, could also become an echo. It bridges the gap between the world within the electronics and the world of the hall."

The second movement, “Heptaechon”, “means ‘seven echoes’ and refers to a large colonnade called the Echo Stoa in the Olympic sanctuary in Olympia, Greece whose acoustics were described by Pausanias in the second century.” It is scored for percussion, piano and electronics.

Kristina writes: “Pausanias said that a word spoken in the colonnade would echo seven times or more. I built a model of the Echo Stoa (because it is no longer standing) based on the excavation plans of the archaeological site. I rendered an auralisation of the acoustics at various locations. My intent in this piece was to examine this site’s peculiar echoing behaviour and to compare an ancient account of sound with modern notions of echo. The somewhat sparse and sharp percussion sounds are intended to mimic the timbres of Roman gongs and chimes. The gongs ring and echo within the sanctuary.”

This piece plays with conceptions of time on several levels. First, there is an attempt to reactivate ancient soundworlds, marrying the past and present. Then, there is the perceived time (duration) spent playing or listening to the work: “There are two types of time in the work. In my view, the sense of time in ‘Ghost Aulos’ is recognisable as form because it was based in the time suggested by the musical material I had created (as I perceived it). ‘Heptaechon’ does not reference musical time. It is more of a walk through a colonnade where ceremonial chimes are being rung. The significance of these sounds and the spaces between them is not intended to be clear to the listener because the cultural meaning was lost hundreds of years ago. The echoes of the echoes are the only thing to hear.” And finally, intervallic beating features prominently in both movements, a function of the acoustics of the aulos and the sounding vessels; by composing with an ear to beating, Kristina is able to transform sustained pitch (often from the vibraphone, the winds and the electronics) into a perceived rhythmic event. Time is being parsed inside the listener’s ear.

P.A. TREMBLAY: (UN)WEAVE

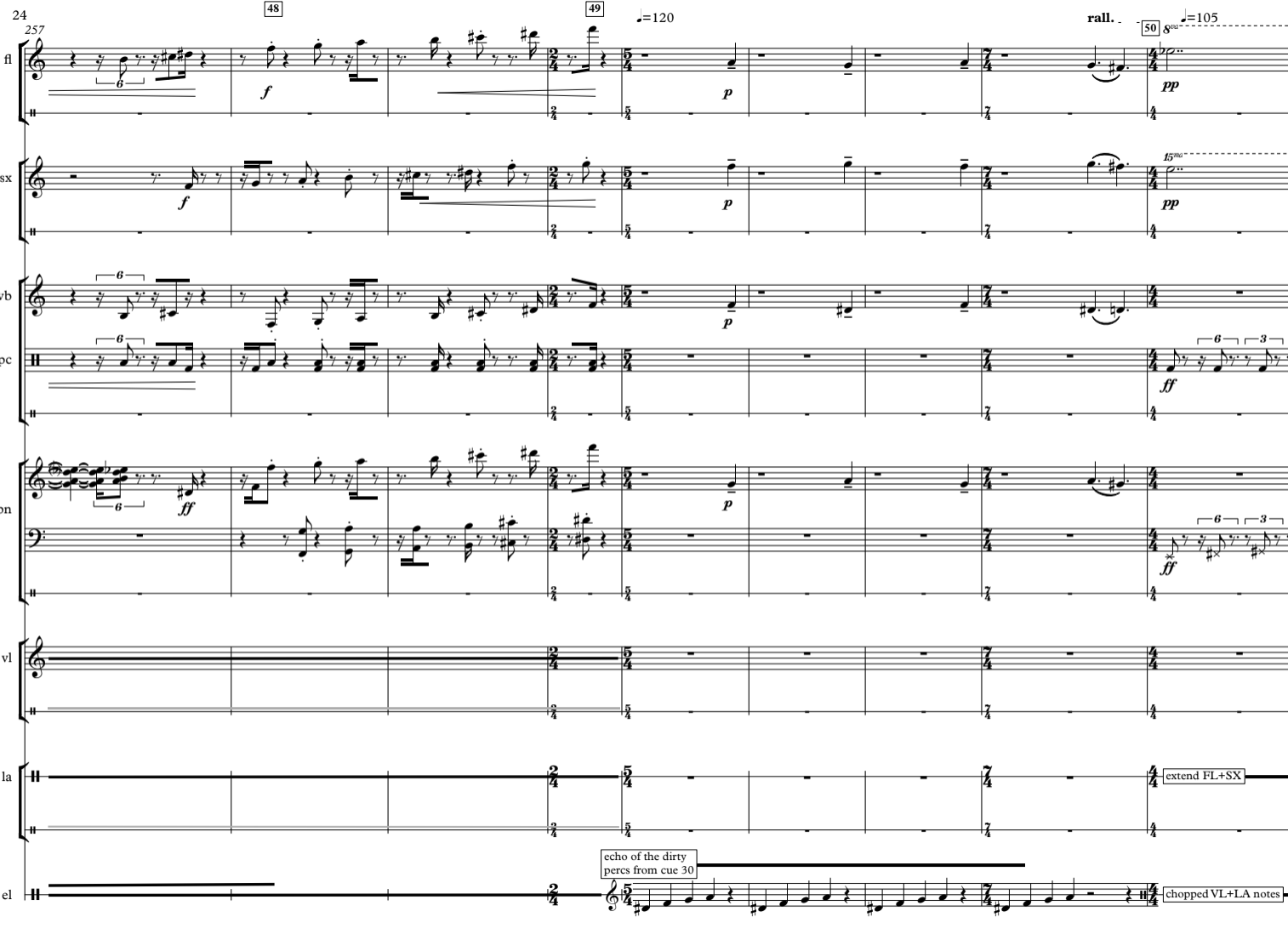

Pierre Alexandre Tremblay’s piece, (un)weave, had already been extensively elaborated in workshops before I joined the project, so my experience was of a much more straightforward score, a monument (so to speak) that we were able to quite confidently rehearse, approach with precision, and perfect. Yet P.A. works dynamically: “I compose in the studio, then turn to workshop material, in a sort of back and forth between ideas and their rendering (how they sound in the room for real), and play with the dialogue between the two: intention/rendition, top down/bottom up, conceptual/emergent.” This method elicits a whole cloud of spontaneity and reaction outside of a preconceived “monument” that keeps the piece from ossifying.

“The instrumental parts are prescriptive because they interlock sonically and rhythmically, with the piano leading the way most of the time”, while the freer material is written for improvisers comfortable with moving boundaries. “I think there is a fragility in the scored material too, from the listener’s perspective – balance [between the instruments] is not trivial, and the precision in the jittery material gives a listening experience of almost ‘spontaneity’,” an improvised feel. This project was also the opportunity for P.A. to write for electronics and processing as performed by Sam Pluta - an unusual circumstance for P.A., who would otherwise simply run fixed media or processes himself. In this case, Sam had more of an improvisatory role while P.A. ran real-time processing, which in some ways was actually more fixed.

When the possibility for this collaboration came about, P.A. decided to explore many of his “obsessions of the moment”, integrating them in what in his words is a “meta-modern integration rather than a post-modern confrontation”. These included “dirty spectralism (distorted, granulated, not as clean and pitch-based, Murail on fuzz), Ikeda-type glitch, Berlin reductionism, downtown groove deconstructed (where free meets dense polymeter) and film editing techniques toward teleologies (especially how simple objects can collapse through transformed repetition and cross-cutting).”

This last element relates directly to my experience of performing the work, which seems to travel on a type of journey, with entire sections in different musical lands. The piece establishes “panels”/“objects”/“strands” (hence the title) that are subsequently mutated and hybridized. “I try to have them explicitly co-evolve. This is where the strength of the film montage theory stimulates me; that field really knows how to pace material in time for a clear narrative effect (even when abstracted).”

In the example above, the “jittery”, groovy material P.A. references builds to a frenzy that is released at the tempo change, taking the scalar material and softening its edges. The sonic object remains, but has been transformed from rollicking big band to ominous lullaby. P.A.’s treatment of time in (un)weave transcends the dichotomy of notated vs. improvised performance, and allows the sounds to tell their own compelling, albeit abstract, narrative.

CHARMAINE LEE: SMOKE, AIRS

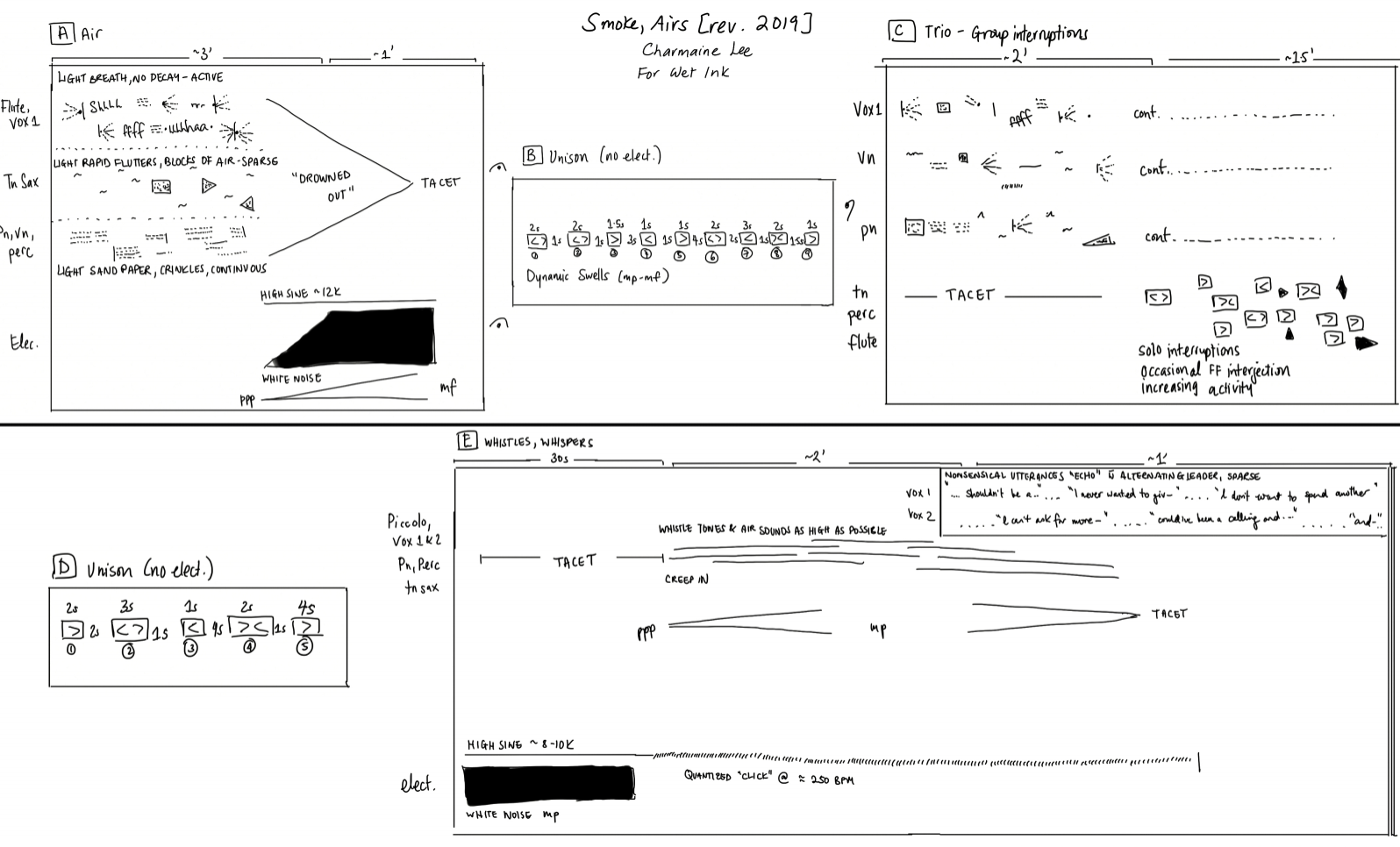

“One of the distinct characteristics I observe between the practices of improvised music vs. notated new music is that the former prioritizes group interaction and sociality over the precise execution of preconceived ideas. 'Success' and 'failure' in the perspective of an improvised performance is largely dependent upon the depth of interactivity rather than a successfully coordinated performance. I think this is a key tension for improvisers working with notation and performers of notated music, and I have often concluded that it is more effective for a piece to either be completely improvised or entirely notated.”

Charmaine Lee’s piece Smoke, Airs, somewhat like P.A.’s, divides the duration of the work into distinct slates. Types of material are given lengths of time that Charmaine, through workshops with Wet Ink, determined would give enough space for interactivity, and more importantly, feel right. In her words, “I wanted to try creating a framework that would open up dynamic group interaction and be supplemented by a score directing key events and macro-level movements of the piece. Since the sound world was heavily inspired by improvisational language, I felt the most effective way to transmit this component of the piece was through aural demonstration.” We spent a good amount of rehearsal time with Charmaine rigorously working through each slate, discovering the sounds that could work together, and how we could develop the material in interesting and interconnected ways in the time she had allotted. We didn’t end up performing this on the clock, however, so small variations set in with each run-through and in each performance.

Charmaine’s practice prioritizes liveness and interactivity, usually in an improvisatory context, so this project was an interesting study in finding middle ground between interpreting a score and allowing material to develop organically through listening. She had very specific ideas not only for the sounding result, but also the energetic direction of the piece, which she needed to communicate to us without hampering our individual abilities to listen, shape and react to sound. Her score gave us just enough guidance, while leaving a lot subject to the moment - and, as it turned out, to the circumstance.

Shortly before leaving for Huddersfield, we found out Charmaine couldn't join us on our trip to England. It was a major bummer on a number of levels (not least of which, I was looking forward to having a lady-buddy on tour), but specifically for her piece, which centers around her voice, her presence and her ability to lead from within the group. Suddenly, I was somewhat “re-cast” as the vocal presence in the piece. Back in New York, we were able to perform the work as composed in December at St. Peter’s Chelsea as intended, with Charmaine. She asked me whether there were “changes in group dynamics, leadership roles, or general energy” between the performances. I think the fact that Charmaine had given us a type of road-map for the piece helped us adapt more spontaneously and, counter-intuitively, with more of a sense of freedom than if the piece had simply existed as an improvisatory contract between the specific group of players. To be completely honest, though, I barely remember either performance of Smoke, Airs - what happened between its temporal borders was internal, present, neither pre-meditated nor re-evaluated. It was its own time.

Looking back on this special collaborative project brings up another wrinkle of time: this was all Before. When we didn’t blink at blowing wind instruments and singing high notes in a small rehearsal space, when we could work until we got hungry or I needed to pump, when we could take a plane and enter the UK. Time has slowed since then, and shown us the layers of experience we may, in our frenzy, have missed. Artists are excavating their archives, triggering memories and explaining experience through whatever records they have - discs, scores, journals, memories... Like today’s archeologists, we are discovering that the ground has shifted on the very essence of our musical study: time. Different explanations of the past are possible and important to the empathetic growth of our society; these records - much like Wet Ink’s recording of these temporally complex hcmf// works - are simply time capsules, just one historical “data set” from which to glean a multiplicity of narratives, experiences, contexts. In many ways, it is a great privilege to take the time to look back, to ask one another questions *after* the gig is over and the record is out. There is still so much to discover.