t’s mid-summer, 2020. Over the past few months of functional unemployment, in the midst of a global pandemic and a powerful surge of activism against our thoroughly racist, broken system, I’ve attempted to self-motivate while navigating waves of intensity from the vantage point of my own tiny boat. All things considered, it’s a good boat and I’m grateful for it. That said, like many of my colleagues, almost all of my work from March into the foreseeable future has been canceled or postponed indefinitely. I’ve had more unstructured time for a longer stretch of days (weeks, months) than any other period of my life literally since I was old enough to sit up. Alongside all of the anxiety, frustration, and grief the state of the world has inspired, this space has also allowed me to luxuriate in my thoughts more than usual, for better or for worse. So when I was approached to write a piece reflecting on my practice, I thought I’d take the opportunity to share some of my current ruminations.

I’m specifically interested in exploring the way I view my art making at the intersections of many collective practices. Mostly, I’ll focus on the influence of feedback, and how positive, negative, or absent feedback has shaped the avenues I’ve historically allowed myself to explore at key moments in my artistic development. In this context, my definition of a collective practice refers to a qualifiable shared medium or mode of expression, and can be as broad as “composing,” or as specific as “composing open form just intonation drone textures for strings.” Feedback can be as formalized as an acceptance or rejection letter to an educational program, and as informal as an offhand comment or a raised eyebrow from an audience member. This is a spectrum with blatant gatekeeping on one end, and unintentional shepherding on the other. Throughout my life, when given the option, I’ve tended to pursue the modes of artistic expression that garner the most praise and external encouragement. Sometimes this is necessary; learning often requires a good deal of support, especially when expensive training and instruments are involved. Additionally, it takes a substantial time investment to get proficient enough at a new craft to be able to incorporate it thoughtfully into a professional context, and it doesn’t always seem worth the effort. It’s easier to keep at it when the perceived starting point is closer to a projected finish line. That said, the work that I’m most proud of has always come as a result of powering through absent or negative feedback, investing the time and energy to incorporate new modes of expression into my practice. This process of addition and folding in has become something of a practice in and of itself, and is an exercise in fostering intentionality when it comes to the directions in which I focus my artistic energy.

There have been a few identifiable junctures over the last decade of what I would consider to be my “professional” life when I decided to incorporate a new sort of collective practice into my own. Each time I started down a new path, there was a steep learning curve, and I invariably put myself in the position of feeling uninformed or amateurish. During these times, I find myself constantly putting my foot in my mouth and ruminating on botched efforts and embarrassing social interactions that reveal my ignorance. This happened within the realm of performance when I was an undergraduate at Oberlin, as I began to specialize in 20th and then 21st century music, and has continued over the last decade as I’ve incorporated composing, ratio derived tunings, improvisation, and performing with electronics into my practice. It’s been the same outside of performance as I began composing more seriously and presenting my work in public.

When I look back at the reasons I got into playing contemporary music in the first place, there are a few factors that informed my decision. If I’m absolutely honest with myself, one of the main reasons was egotistical; my perception of the culture at Oberlin was that only the top players got to play with the Contemporary Music Ensemble. When I entered my first year at Oberlin, I felt that my technique was behind that of many of my studio mates, and I rarely received overtly positive feedback about my playing from my teacher. It was an ego boost to be asked to play with CME as a sophomore, and it made me feel included in an elite niche within the classical world. In the following year or two I was accepted into a few summer festivals focused on contemporary music, and I took these acceptances as a validation of my newfound identity as a “new music person.” I applied to the Contemporary Performance Program (CPP) at the Manhattan School of Music (MSM) for my masters, was accepted, and that led to enough work to sustain me and solidified my reputation within the classical music community as a new music specialist. Just after I finished my masters, I was invited to premiere Ryan Pratt’s K. Tracing with the Wet Ink large ensemble as concerto soloist. This was my first time playing with Wet Ink, and it was majorly affirming to be invited to perform as soloist with such a well established professional ensemble.

Ryan Pratt: K. Tracing, premiere performance at The DiMenna Center

My next major frontier was composing. I’d been composing independently since high school, but hadn’t shown my sketches to anyone for years. There were a few reasons for this, none of which were very good and all of which were based on feedback. First, I’d applied for a prestigious summer program in composition as a high school senior and was rejected. Next, when I got to Oberlin I realized how little I knew about the field of contemporary composition, and felt that I couldn’t contribute until I was more educated and aware of the possibilities. In short, my imposter complex led me to shut down the impulse to compose entirely. There was also some deeply internalized gender bias at play, which I sometimes still find creeping around my psychic space in all kinds of insidious ways, despite years of conscious unlearning.

I’m not sure what finally propelled me to complete a piece after all those years of hidden sketches, except that I’d known for a long time that I wanted to compose and I saw an opportunity. There was a shadow of intentionality at play in this decision, but it was more like a compulsion that finally saw a potential outlet. In my second year at MSM, I had the good fortune to take a few composition lessons with [former Wet Ink co-director] Reiko Fueting as an independent study, and it was in that time that I composed memory on the unbroken figure for myself to play with my group TAK ensemble. We had just formed TAK less than a year before, and I was able to recruit these excellent musicians to perform it with me. I opted to score the piece for violin with “mostly untrained voices,” largely because the task of writing a quintet was daunting enough without adding flute, clarinet, and percussion to the mix, which I felt I knew very little about.

About two years after I wrote memory on the unbroken figure, I decided it was terrible and I took the recording offline. I initially hesitated to share it here, but it marked an important moment for me: this was when I officially folded the collective practice of composing into my artistic identity. Listening back now after all these years, I actually quite like it. I even hear the seeds of some of the musical language I’m still interested in.

As a composer, my string quartet (The Rhythm Method) has hands down been my greatest source of positive feedback and encouragement. Over the years, the quartet members have composed a substantial portion of the group’s repertoire, and we aim to create opportunities for workshopping and performing each others’ work as often as possible. If not for the quartet, I’m not sure that I would have continued composing publicly, or at least I would be a very different composer than I am today. It was primarily through this collaborative relationship that I found a safe space to experiment with broadening my compositional toolbox, incorporating elements like graphic notation, vocalization, and ratio derived tuning (just intonation).

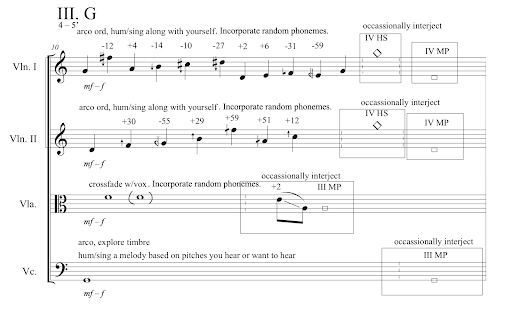

We premiered the most recent piece I wrote for the group, string quartet no. 2, in mid-March, on the last concert we played before the shutdown. It incorporates a number of elements I’ve been folding into my practice for some time: just intonation harmonic structures, vocalization, and open notation with text instructions. This is one of my most minimal scores; the entire fifteen-minute piece is contained in four systems.

string quartet no. 2, live recording of premiere, performed by The Rhythm Method

Within the broader collective practice of “composing” there are numerous identifiable niche practices that require additional specialization and familiarity with existing systems. One of these is the use of just intonation (JI). For the sake of brevity and inclusivity, I’ll define just intonation as any tuning system derived from the ratio relationships endemic to physical acoustics, as expressed in the harmonic series. When I first encountered JI, it blew my mind. The elegance and logic of conceiving of harmony through physical ratios was a revelation. The standard of equal temperament is a conspiracy. Difference tones? Otoacoustic emissions? Sign me up.

In addition to loving the sound of JI harmonies on an aesthetic level and appreciating their grounding in the physical world, I had the impression that composers who worked with JI were exceedingly cool and smart. When I first took an active interest in JI, my imposter syndrome was strong; every time I tried to learn more by talking to people who knew about it, I felt like an idiot. I don’t know that I would have pushed through this phase had it not been for my dear friend Austin Wulliman, who is at least as big a nerd as I am and happened to be my housemate at the time. Austin plays with the JACK Quartet, which is one of the best new music ensembles in the world when it comes to precision in JI tuning. His positive encouragement and generosity in sharing a vast reservoir of knowledge was instrumental not just in my ability to understand the underlying concepts of JI, but in building the confidence to implement this tuning system in my compositional work. A lucky circumstance of friendship provided the support and resources I needed to pursue this new mode of practice, but looking back I can identify that the impulse to study and follow through with it was extremely intentional. Some years later, this is perhaps the most important aspect of how I conceptualize pitch, both in my writing and as a performer.

Improvisation has been another massive addition to my practice in recent years. This was another area in which my respect and awe of great artists had the effect of inhibiting my efforts at incorporating it into my own practice. I’d tried my hand at jazz improvisation a few times during my undergrad, and received subtle but generally negative feedback across the board. Rather than putting in the hours to get better, I decided to focus my energies elsewhere. I was already crying after half of my violin lessons because I felt frustrated and inadequate – why embarrass myself any further? It wasn’t until some years later that I found myself at a noise show in the dirty back room of a bar in Berlin. My friend was playing a set, and I don’t remember exactly what he did but it was something like bowing and plucking an amplified birdcage and screaming death metal style into a microphone, and there was some guy rolling around on the floor and dancing like an enchanted robot. Once again, I had the revelation: these are my people.

When I got back to New York, I started showing up to more shows like this and developing my own practice in private. I went to see live shows as often as possible, and was inspired by the slew of excellent performers coming from all different improvisational backgrounds and practices that I was able to hear at intimate living room, basement, or back room gatherings. Entering into this space wasn’t as scary as I’d thought it would be; the shows in this scene usually have an audience of about ten or fifteen people, so they’re pretty low-pressure. That said, building an improvisational practice is an ongoing journey for me, and it’s only been possible because of inspiration, encouragement, and collaborations with other artists working within similar or adjacent aesthetic frameworks. Improvisation is an especially rich and variegated collective practice, because of the limitless networks of interconnected practices that feed into each individual improviser’s expression of artistry. Once I pushed through my initial insecurities and fear of rejection, this mode of performance that had at first seemed daunting became an outlet in which I can feel completely free, and an integral aspect of my artistic practice as a whole. A few months ago, as venues began shuttering their doors, I co-founded a facebook group that hosts an online weekly gathering for improvisers. Below is a live streamed set I performed with Brandon Lopez on the series last weekend.

Brandon Lopez and Marina Kifferstein performing on the Open Improvisations web series

Recently, with the memory of live concerts growing more distant every day and no clear end in sight, I’ve decided to explore a new frontier in the development of my practice. During this time of remote work and social distancing, I’ve been drawn down a rabbit hole of learning to produce electronic media, and I've spent many hours laboring over tutorials to learn how to generate, record, stream, process, and edit audio and video. I have yet to achieve fluency with any of these programs, but I’ve made some modest gains. I work with experts in electronic media on a regular basis, but I’ve never put in the time to learn how to generate my own product from start to finish. In past attempts, I’ve been easily discouraged; I felt the learning curve was too steep and I would just make a fool of myself if I tried any harder. The pressure to generate socially distanced art brought me back to this pursuit with more intentionality and commitment, and the encouragement and resources I’ve received from friends has been massively beneficial to my progress. I still have a lot to learn, but in May I was able to produce my first electronic set with original video for an online show presented by Rhizome, a wonderful venue in D.C.

Solo set, presented by Rhizome

Artistic practice exists in the dialectical space that encompasses an individual and her environment. The conditions of my environment and my community support systems have been influential not only in providing the necessary tools to carve my own path, but more importantly in the selection of the kinds of tools I believe I want to use, and the manner in which I feel licensed to use them. In a recent Helga Davis interview with Esperanza Spalding on the Helga podcast, Spalding describes “originality” in terms of its etymology; the “origin” is the community and circumstances we’re born into, and the rest of it (the “ality”) is the direction we take everything we’ve been given, as a creative individual. The point of origin is ever-evolving over a lifetime, and changes with each set of conditions and community support networks surrounding the development of an artistic idea on both local and global levels. This is all to say that art does not exist in a vacuum, and neither does the artist.

The word “intentionality” might be deconstructed in the same way; the “intention” can exist, but without the “ality,” meaning what we do with that intention, it goes nowhere. We are all responsible for our choices, and being aware of the role our surroundings play in decision making can help guide future steps with deeper intentionality. There is an inherent discomfort in being bad at something before getting good at it. Looking back, I think I've gotten more comfortable with (and better at) being bad at new things, in order that I might someday be better at them. This meta-practice is an exercise in fostering deeper intentionality in shaping my artistic practice as a whole.