he four artists represented in this issue's archival concert – Lea Bertucci, Darius Jones, Ingrid Laubrock, and Charmaine Lee – work primarily in and between traditions where the coexistence of improvisation and composition within a musical form is not radical, but assumed.

And, looking broadly at the musical community today, it’s clear that musicians in almost every stylistic territory have developed practices that balance openness and structure in various ways, to various aesthetic ends. In fact, it starts to seem like the outliers are actually the scenes that are particularly orthodox about not mixing the two, either insisting that all elements be both notated and invariant (as in most European classical music and the large majority of its descendant aesthetics in new music), or seeing any elements of fixed, replicable structure as suspect (as do some of the more ideological communities in free music).

In the wide space between these poles, there's an entire continuum of approaches that seek to balance composition and improvisation. For me, some of the most exciting music I've encountered in recent years lives in this intermediary, hybrid space, combining specifically predetermined musical elements with others that are open and available to be shaped spontaneously, with full attention to the here-and-now reality of the moment, space, and situation.

The following list compiles some of my recent and personal favorites, with a focus especially on composers I feel are deserving of broader recognition, both generally and within the world of new music. Each piece situates itself at a particular point on the continuum between fully fixed and completely free; each offers a different balance of predetermined structure and in-the-moment responsive listening and decision making. Taken as a whole, my hope is that this music can offer to a new music audience some much-needed provocations and challenges to assumptions about notation, complexity, the compositional craft of improvisers, and the political forces and structures replicated in and set in motion by our ways of working and making music.

1. Luke Stewart - Works for Upright Bass and Amplifier

2. James Fei - Horizontal/Vertical, from Alto Quartets

3. Kaja Draksler - Danas, jučer, sutra

4. Anthony Braxton - Quartet (Santa Cruz)1993

5. Mauricio Pauly - The Threshing Floor

6. Nate Wooley - Seven Storey Mountain VI

7. Eliane Radigue - Occam Ocean

(additional works by Ingrid Laubrock, Darius Jones, Lea Bertucci, and Charmaine Lee are collected below, and links to further suggested artists and recordings are embedded throughout the article)

1. WORKS FOR UPRIGHT BASS AND AMPLIFIER

————Luke Stewart

Luke is an amazing person and musician – a bass player, composer, organizer, and activist, he's a central and galvanizing presence in experimental jazz and improvised music in D.C. and New York. I love this record – among its other merits it's one of the most compelling, detailed, sensitive explorations of feedback in an instrumental context that I've come across. (I also love Alvin Lucier, but if you're at an institution and planning on teaching his music this year, you could consider teaching this instead...or, also!)

Stewart's use of feedback in performance deserves special mention, as it provides a concrete instance of the benefits of treating certain musical materials with an open, responsive, improvised practice. While much of the form and material of Works for Upright Bass and Amplifier is composed, the local-level management of the feedback is a dance of constant adjustment – rocking the bass toward and away from the amp, tweaking the EQ, finding zones of almost “multiphonic” instability and attempting to balance within them. Trying to pre-determine and compose out every detail of these would inevitably result in structures utterly non-responsive to the reactions of a system that is simultaneously delicate and wild, requiring continuous attention and dialogic engagement.

And so, with a material like feedback (or other “wild,” “raw,” or “perishable” sound-types), you can shape it up to a point, but it's very difficult to predict exactly how it will behave in performance. Can you still find a way within a piece to give a material like this the space to be itself?

see also:

Toshimaru Nakamura - nimb series

Eliane Radigue - psi 847

Cathy van Eck - Wings

more about Luke Stewart:

https://wfubaa.bandcamp.com/

2. HORIZONTAL–VERTICAL, FROM ALTO QUARTETS

————James Fei

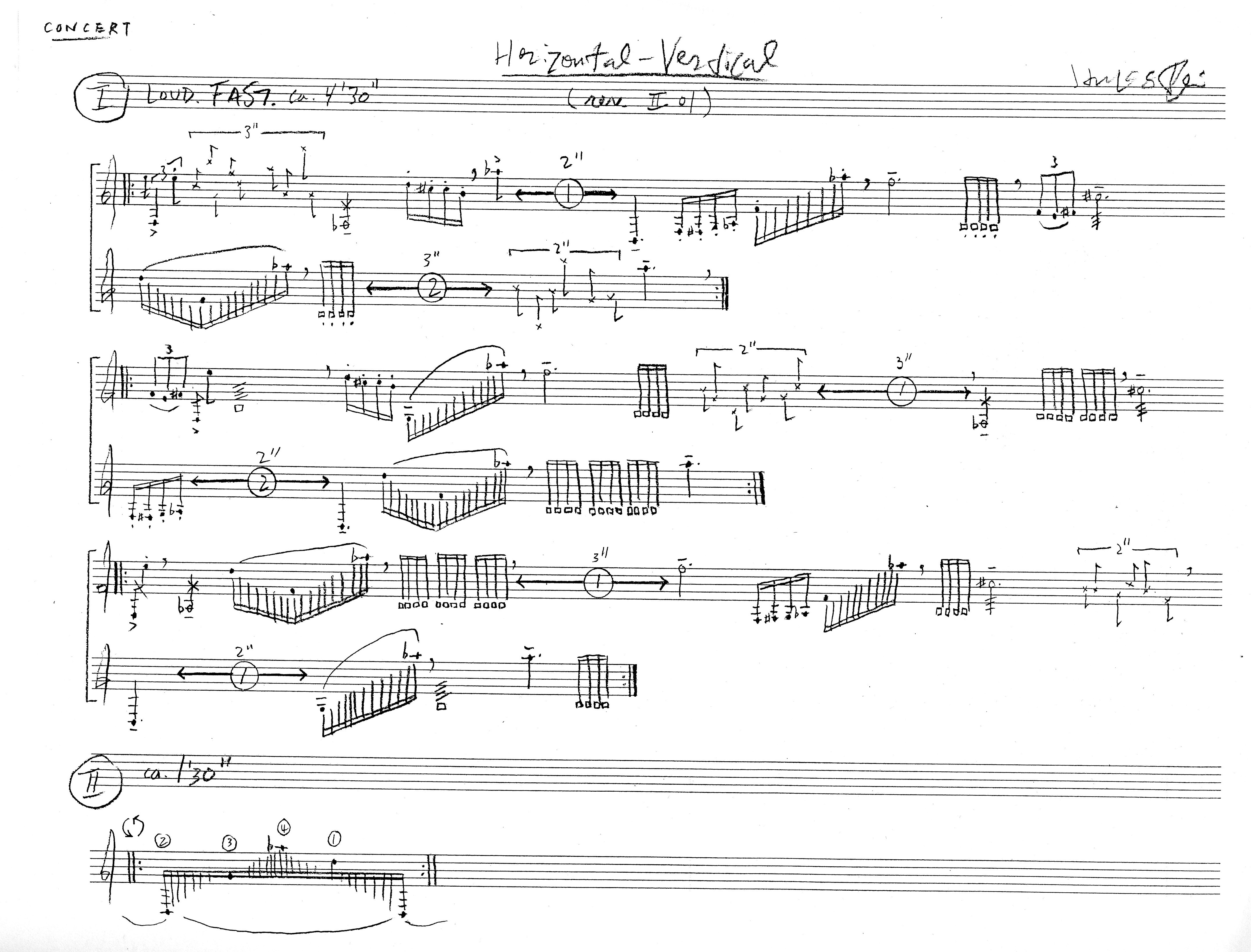

James Fei is a composer, saxophonist, and live electronics performer. His 2004 album of textural and timbral studies for four alto saxophones has been a continuous source of inspiration and pleasure for me since it came out (so much so that I hope James will forgive me for talking about it in public yet again).

In Horizontal–Vertical, a small collection of high-energy gestures and motives attains a quasi-sculptural presence through constant cyclical reassertion, like light coalescing in a time-lapse photograph. Every time I come back to this piece I'm amazed at the elegance and efficiency of James's notation – seven lines of music generates all this! – and the skill in systems design required to imagine a monophonic line that, when played against itself, explodes out into harmonic motion, complex texture, and registral saturation (after all, this is basically a canon).

Again, think of an analogous texture in a fully notated piece (by Beat Furrer, e.g.), and consider the relative merits and trade-offs of arriving at similar results through their various performance practices. Or, take an even more concrete example: Ligeti's Atmosphères (for large orchestra) and Volumina (for solo organ), both from 1961-2. Listen to them back-to-back and it's hard to miss that they're versions of each other, with the creative, fluid, highly open graphic notation of Volumina necessarily fixed and specified when translated to the medium and performance practice of the orchestra. Notation, as a technology, is great at organizing and synchronizing groups of people, and serves as a powerful mnemonic tool, so those forms of organization can be repeated. But it's not always necessary that it function at the same level of resolution, or that it always grip the music and steer it to exactly the same form every time.

In any event, it's not a simple question of choosing one approach over the other, and fortunately you don't have to. But the idea that Fei's piece is somehow less “authored” or intentional in its details as a result of being realized by improvisers strikes me as pretty unpersuasive.

see also:

Anthony Braxton - Echo Echo Mirror House

Peter Ablinger - Verkündigung

more about James Fei:

https://www.jamesfei.com

3. DANAS, JUČER, SUTRA

————Kaja Draksler

A beautiful piece, wonderfully confident in its simplicity, gradually less and less simple, ultimately intense and affecting. Kaja Draksler, a Slovenian pianist and composer based for many years in Amsterdam, brings a hybrid background in jazz piano and classical composition to her projects, which range from groups as a leader and composer (Kaja Draksler Octet), to solo performances, free improvisation, duos with other young European luminaries such as Susana Santos Silva and Eve Risser, and small-group collaborative bands.

In Danas, jučer, sutra (written for and performed by her Octet), a descending, helical, Shepard-tone-like figure in the viola and bass cycles continuously, underpinning simple melodic figures from the voices. As the piece unfolds, saxophonist Ada Rave embarks on a remarkable slow-burn improvisation on prepared tenor, at first just adding a little bit of grit to the texture, eventually overgrowing the cycling lattice with a series of wrenching noise statements. Draksler's incorporation of improvisation into the composition is especially subtle and restrained, and her trust in her bandmates’ creativity finds full validation in the specificity with which Rave realizes the functional and expressive work the solo has to do in the piece.

4. QUARTET (SANTA CRUZ) 1993

————Anthony Braxton

Anthony Braxton Quartet: Anthony Braxton, winds Marilyn Crispell, piano Mark Dresser, bass Gerry Hemmingway, drums/percussion

Anthony Braxton's quartet music represents a pinnacle achievement in a hybrid practice of true fluidity between composition and improvisation. It feels a bit odd to think of a figure of Braxton's historical stature as under-recognized, but for the fact that, upon reflection, he so clearly is! It's long past time for new music to take Braxton seriously as a composer; maybe it's starting to happen a bit among ensembles, but the institutional level has remained pretty woefully silent, for reasons that range from racism (structural and otherwise), to misunderstanding, to a kind of technocratic condescension towards any art that partakes sincerely of mysticism and spirituality.

Braxton's quartet practice, refined over years of touring, threads together sequential and simultaneous layerings of composed and improvised material into cohesive set-length statements. Within an overall modular structure, Braxton plugs in “primary territories” of notated compositions for each set (many of which extend to dozens of pages long) that form a basic road-map, between and around which the musicians navigate with varying degrees of freedom: improvising freely, improvising within Braxton's post-serial, parametric “Language Music” framework, and collaging earlier solo pieces and duo compositions with rhythm section “pulse tracks.”*

In assembling the materials for these modular forms, Braxton's compositional insight seems to have been that to construct a space rich and dense in its polyphony of objects and possibilities, it helps to be systematic in categorizing those objects and possibilities according to their relevant perceptual attributes. As a result, Braxton can construct complementary sets of materials, where one element’s most salient features don't obstruct those of another when they’re collaged, but instead leave space, creating polyphony and transparency instead of interference.

Further, the pacing of the episodes remains completely flexible, each successive composition fired by a cue from Braxton. This context – cue-based, open and responsive to the moment, freed from the implicit click-track of a score that needs to manage the synchrony of every second of the music – offers a maximum of possibilities for shaping the form and proportions of each modular meta-composition in real time.

*Braxton's “pulse track” structures are a fascinating microcosm of the fixed/free binary: fully notated rhythmic figures alternate in strings with bracketed durations of open improvisation, all in time, constantly spinning out and snapping back into unison. The result has an incredible feeling of tethered, centripetal energy.

see also:

Roscoe Mitchell - Sound

Matt Mitchell - A Pouting Grimace

Henry Threadgill - Dirt… And More Dirt

Paul Steinbeck's analysis of Braxton's Composition No. 76

more about Anthony Braxton:

5. THE THRESHING FLOOR

————Mauricio Pauly

By far the most notated and detail-specific music on this list – extremely so! with like, custom notational strategies for the Boss Digital Delay and Octave pedals the players use... – Mauricio Pauly's The Threshing Floor provides an exceptionally successful and creative example of a piece that remains squarely within the aesthetic framework of new music without walling itself off from uncertainty, variability, and risk.

As with many of the recent new music works that I find most convincing, The Threshing Floor is the product of a direct collaborative process with specific performers (in this case, Joshua Hyde and Noam Bierstone, of the duo scapegoat), and the surface complexity of the notation speaks of a level of detail and concreteness that comes from a long process of refinement of actual, rather than simply imagined, sounds. There's an extreme, curated specificity to Pauly's materials, all the more apparent due to his open and unclenched deployment of them within the time-flow of the music. The sounds are given space to arise, to be and be appreciated, to be shaped and responded to, and many of his performance instructions in the score manifest this unusual, welcome flexibility: “rest and listen,” “play around with tempting feedback, never let it blow out,” “improvise recovery.”

Pauly's piece also provides an answer to the earlier rhetorical question (in re: Luke Stewart) about finding an open context in a notated piece to let feedback function as a material – here's a clear, effective example of a way.

see also:

Evan Parker / Paul Lytton - RA

Chris Pitsiokos and Tyshawn Sorey, Spectrum, May 13, 2014

Giorgio Netti - works for saxophone

more about Mauricio Pauly:

https://mauriciopauly.com

6. SEVEN STOREY MOUNTAIN VI

————Nate Wooley

Seven Storey Mountain VI

Nate Wooley (trumpet), C Spencer Yeh (violin), Samara Lubelski (violin), Ben Hall (drums), Chris Corsano (drums), Ryan Sawyer (drums), Emily Manzo (keyboard), Isabelle O’Connell (keyboard), Ava Mendoza (guitar), Julien Desperez (guitar), Susan Alcorn (pedal steel guitar)

and Mellissa Hughes, Kamala Sankaram, Anne Rhodes, Bridget Hogan, Daisy Press, Anaïs Maviel, Christina Kay, Shannyn Rinker, Aubrey Johnson, Yoon Sun Choi, Lisa Karrer, Dafna Naphtali, Amirtha Kidambi, Jasmine Wilson, Samita Sinha, Ariadne Greif, Nina Mutlu, Holly Nadal, Kirsten Sollek, and Erica Koehring (voices), directed by Megan Schubert

In an interview in Joe Morris's The Properties of Free Music, composer, improviser, and self-effacing trumpet virtuoso Nate Wooley describes one facet of his approach:

“I think of the other players as objects that are spinning. Players A and B have material. It spins at a certain rate and in a certain direction. I, as player C, am aware of the material and the speed in which it's spinning, and I choose to present my own material at my own rate of spinning, but I can also be affected by your material […] That way everything moves like an organism, each player projecting their own specific idea, but also being affected by the other players involved in evolving the organism.”

Some aspect of this “spinning,” of individuals circling each other in long polyrhythmic orbits, free yet connected, seems to underpin Nate's Seven Storey Mountain VI, the most recent chapter of his seven-part “song cycle” for large ensemble. Wooley balances structured and open elements beautifully, with a respiratory organicism to the local-level pacing that unfolds around a taut through-line of escalating tension, arriving finally to a high plateau of saturated intensity.

Seven Storey Mountain, having expanded to thirty-two musicians in its most recent iteration, offers a beautiful new concept for what “orchestral” music could be – collectivist, personal, non-hierarchical, valuing individuals for their differing talents and experiences, yet also creating contexts in which all of the individuals can work together as a larger force of group energy. It's a model perfectly fitted to Wooley’s vision of the project as a vehicle for a kind of collective secular catharsis, aiming, in his words, “to create a sense of ecstatic joy and emotional release that is purely human; made by people for people.”

see also:

Bill Dixon - Tapestries for Small Orchestra ,

Susan Alcorn - The Heart Sutra,

more about Nate Wooley:

7. OCCAM OCEAN

————Eliane Radigue

Occam Ocean: performed by ONCEIM

One of the most fascinating developments in composition in recent years, for me, has been Eliane Radigue's transition from electronic to acoustic music. A pioneering and hopefully-at-this-point canonical figure in electronic music, in the early years of the 21st century Radigue turned away from her instrument (the ARP synthesizer) and previous methods and practices and began writing acoustic chamber pieces in close collaboration with chosen performers (among them Charles Curtis, Rhodri Davies, Carol Robinson, and Nate Wooley).

According to violist and Radigue-collaborator Julia Eckhardt, “[t]he transmission of a work of Eliane's is done orally and mentally through words and an image, without a physical representation.” That is, there's usually no score – a work-concept whose radicality within the framework of new music (still primarily situated in the academy and dominated by its text-centered traditions of knowledge) is difficult to overstate.

In the case of the Occam series, the development of a piece is “guided by an image of moving water,” against which a set of other images and ideas are placed, among them a comparative diagram of wavelengths (from interplanetary to nanometer scale) that Radigue encountered at the Natural History Museum in Los Angeles, and William of Ockham's motto “the simplest the best” (“Occam's Razor”).

Occam Ocean, the fruit of a two-year collaboration between Radigue and the Paris-based Orchestre de Nouvelles Créations, Expérimentations et Improvisations Musicales (ONCEIM), brings these images to an orchestral scale. In addition to the total concentration, patience, and raw, material beauty of sound that make Occam Ocean so compelling, the image of collectivism, distributed authorship, and committed agency presented by the musicians has the effect of manifesting, temporarily, a social and political structure that stands in almost complete opposition to those generally in effect in contemporary American and European society. As more and more groups pursue these types of situations – see also Splitter Orchester in Berlin, Magnus Granberg's Skogen, Heroes are Gang Leaders, as well as Wooley's Seven Storey Mountain – they begin to set into motion waves of influence, seeding possible futures into the landscape until the possibility of their realization stops seeming utopian and starts to feel necessary.

see also:

George Lewis and Splitter Orchester - Creative Construction Set

mathias spahlinger - doppelt bejaht (etudes for orchestra without conductor)

Tyshawn Sorey - Pillars

Heroes are Gang Leaders

Skogen - Despairs Had Governed Me Too Long

more from this issue's artists:

Ingrid Laubrock - Contemporary Chaos Practices

Darius Jones - The Oversoul Manual

Lea Bertucci - Acoustic Shadows

Charmaine Lee - a stone widens it