y mission as a composer/improviser has for a long time been combining both disciplines in ways that seem meaningful, varied and interesting to me – giving each equal weight and respect. It can be a challenge to combine what is essentially in the past and present. Though the composer is in the present while writing, by the time the piece is played its creation is in the past and the performance becomes a reproduction – usually with fixed and detailed ideas of what it is supposed to sound like. In contrast, improvising means dealing with a substantial amount of musical information in real time and making decisions that alter the course of the music, often intuitively and extremely fast. There seems to be a dichotomy in improvisation: on the micro level there is rapid, split-second decision making and an acute sense of hearing everything in the room — not just pitch, timbre and rhythm, but also where the sound is located. On the macro level there is a calm and almost detached part of myself which observes the bigger picture and overall shape of the piece. While improvising, it almost feels like my being is split in half: one side focusing on detail in a quasi subconscious way, the other taking care of the overall shape of the music.

When composing music, I feel a certain sense of luxury about having the time to access and capture my imagination slowly, and then expand on these ideas and focus on details. If a composition involves improvisation, I tend to think of strategies that allow the musicians to express themselves and act as 'sub-composers' while leaving me in charge of the overall course of the music. Sometimes I direct by playing in real time and at other times the preconceived compositional framework provides that function. Often, it's a combination of both.

Most of the time in my compositions, the choices musicians make in improvised sections are completely open, although there are exceptions. My background is in Jazz, and I particularly admire composers like Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus, who are very aware of their band members' individual voices and compose perfect 'concertos' for them. Mingus' compositional skills meshed with, for example, Eric Dolphy, George Adams or Don Pullen's playing, while Ellington’s music incorporated Johnny Hodges' and Paul Gonsalves' voices (along with everybody else in his band). These were exceptional marriages of minds and souls. I put a lot of thought into the musicians I pick for my groups or recordings, especially when the ensemble is relatively small. Living in NYC means being in the fortunate position of being able to find the right voices for just about anything one imagines. There is a great pool of highly skilled musicians from varied disciplines, who have a shared sound world, ideas and aesthetics and are willing to learn from each other respectfully. Once I have put a group together I tend to keep the performers' sounds in mind while envisaging frameworks for their personalities to emerge.

The following is about integrating improvisation into my composition Drilling, recorded on my 2020 record Dreamt Twice, Twice Dreamt. I chose this particular piece as it incorporates several approaches of integrating free improvisation into composition, all of which affect the piece’s texture and rate of development in different ways. On the recording there are small and large ensemble versions; here I dismantle the small group one.

All the compositions on the record are inspired by dreams. The one that inspired Drilling goes like this: An elderly couple invited me to their house. It's the husband's birthday and we're about to celebrate. However, he has a splitting headache and says he needs a hole drilled into his skull to relieve the pressure. He asks me to do it and I agree. The drill bit has the diameter of a quarter. Enormous! I drill into his skull, but make sure the bone stays attached so that he can just close the hole with the hinged bone acting as a lid. He is still in agony and asks me to do it again and again in different places. I comply, but seem to have lost my touch: the holes get deeper and deeper and the bone fragment “lids” start falling inside the wounds. Every time I drill a new hole into his skull the crunching sound gets harder to bear. Eventually, I stop and he says he'll be fine. I feel terrible. The next day the wounds have swollen into humongous pustules. I tell him that he should go to the hospital to make sure there is no infection, but he still says he'll be fine. I suddenly realize that what I did must be illegal, even though he asked me to do it. I panic.

Trepanation – the drilling of holes in human skulls – immediately came to mind when I woke up after this particularly disturbing dream. It has been around for seven thousand years and was practiced all over the world. The jury is still out as to whether it was done for purely medical reasons or if there was a ritual aspect to some of the cases. There was nothing soothing about this dream, and as I meditated on it before sitting down to compose, the same feeling of darkness overcame me. Yet, I realized there was a sense of mutual understanding between the old man and myself. I was after all trying to help him to ease his pain, although I felt extremely uncomfortable while drilling (and was also apparently very bad at it). It was a real conflict and the fact that what I was doing is illegal just added to the sense of dread.

The opening section of Drilling is a layered accordion drone consisting of four clusters, three of them doubled using different timbral registers for variety. The drones enter one by one in a loose order of darkness. First, a dense left hand cluster that accordionist Adam Matlock and I agreed on by trial. This is followed by chromatic clusters, then only white keys, and finally pentatonic, using black keys only. All layers grow in volume at different ratios, culminating in about twenty seconds of triple-forte before subsiding again – one by one, in the opposite order. The effect is that the clashing overtones change throughout the piece. What at first seems an impenetrable wall of sound reveals texture and variation from within over time. At the other end, Zeena Parkins (electric harp) and Josh Modney (violin) emerge, as if parting a curtain.

This whole following section (Drilling, part 1) is very gestural. It begins with a joint open improvisation by Zeena and Josh. The only instruction for the musicians was directly related to the dream:

This is based on a dream I had about drilling holes into someone's skull because he asked me to. I complied, but part of me knew it was wrong the entire time. The harp should reflect the conscious "drilling" person, the violin the subconscious, less tangible part that is more fragile but can't be shut out.

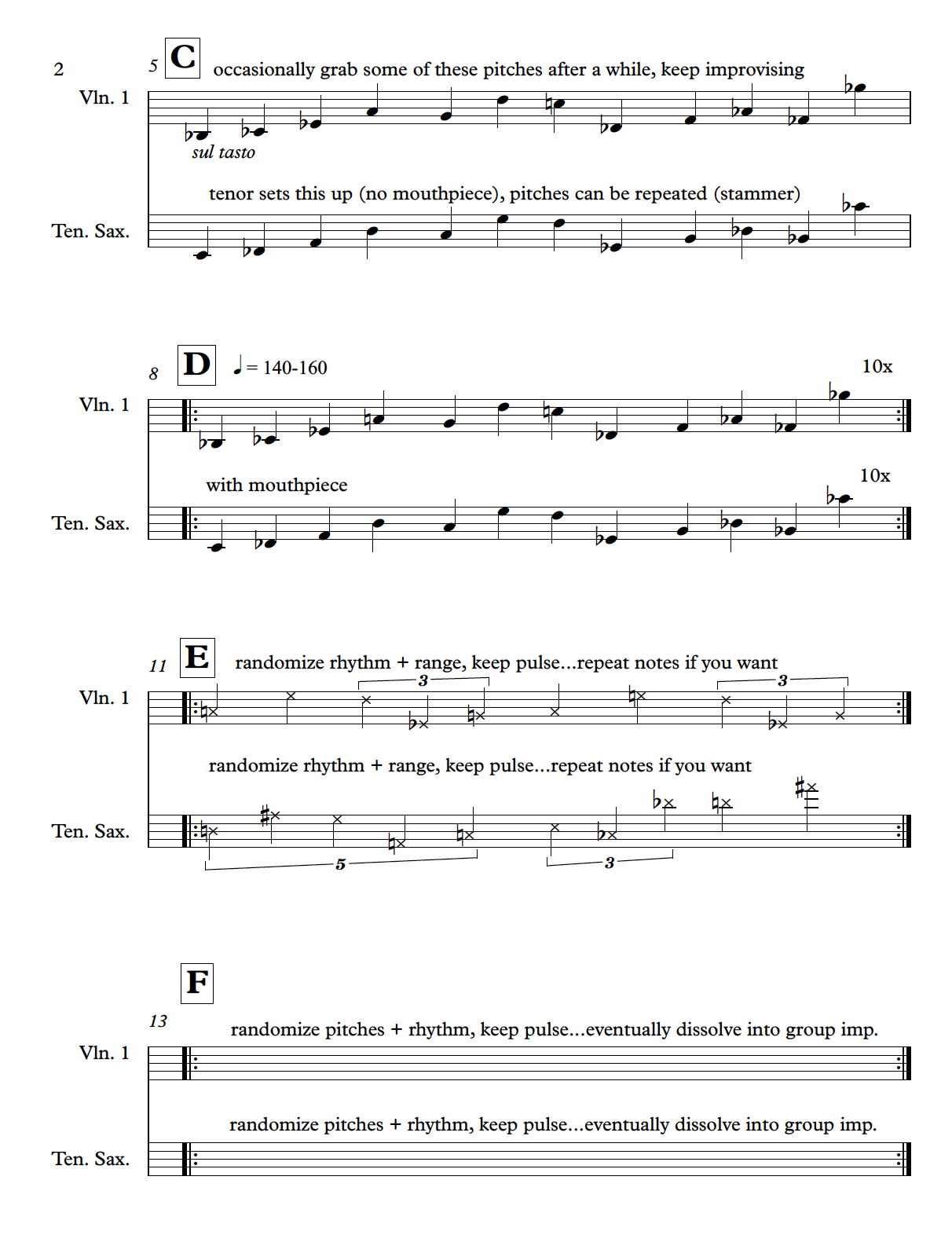

What happens next on the recording is really an example of how being flexible as a composer can improve the music and make it more expressive and flowing. Below is the relevant part of the score, as I imagined it. I deliberately kept it relatively nonspecific and, to a degree, open for interpretation, but the music was meant to have a definite arc and sense of development. We recorded three versions, each one moving further and further away from the instructions. I liked all of them, but by far preferred the last one where we are merely grazing the material – Josh playing it super quietly, fleetingly and with a lot of timbral variation, Cory [Smythe] scratching the piano strings with a credit card using the up and down movement of the intervals but not necessarily the pitches, and me weaving in and out of the whole fabric. I had always meant for Zeena to have the improvisational wild card throughout, but by not forcing the rest of us to follow a certain curve, the result is much more interactive, mysterious and satisfying to me.

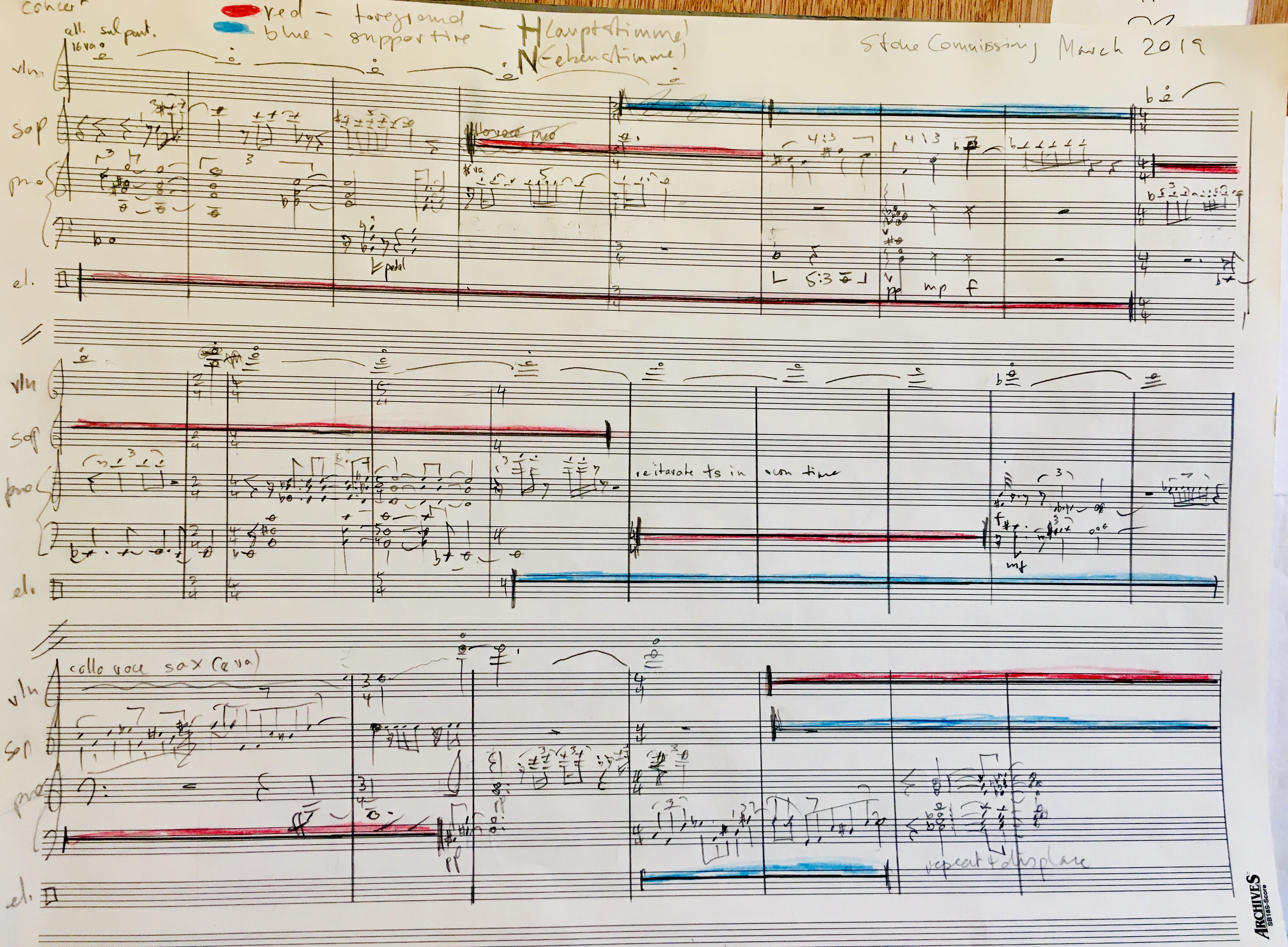

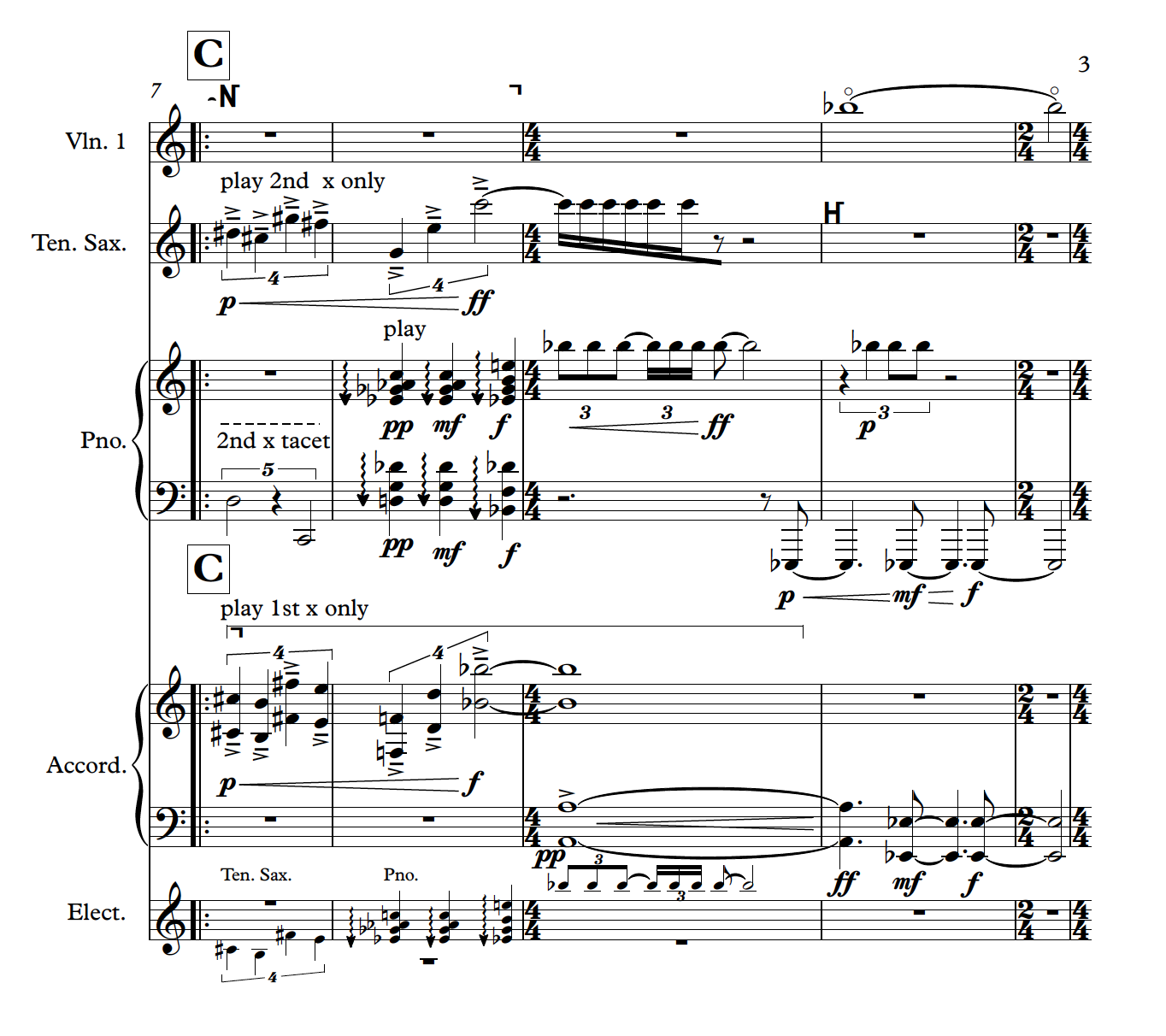

Drilling, part 2 is the main body of the piece. The electric harp is replaced by accordion and electronics (Sam Pluta), otherwise the instrumentation remains the same. My main strategy to connect improvisation and composition here is to include short 'portals' for improvisation with defined lengths into what is otherwise a tightly composed piece. These improvisations get passed around the group and are often duets or trios, but with staggered entrance and exit points to blur the edges between composition and improvisation ever further. It's like individual voices popping out of a crowd for a second before subsiding in collective murmur again. I used my more intuitive sensibility as an improviser to decide how long these moments should be and also specified whether the player's role is the one of a soloist or whether it has an accompanying quality. In the first draft – not yet including the accordion – the soloistic parts are color coded red, while the more accompanimental ones are blue. In the final version I used symbols representing the German terms Hauptstimme and Nebenstimme (“main voice” and “secondary voice”).

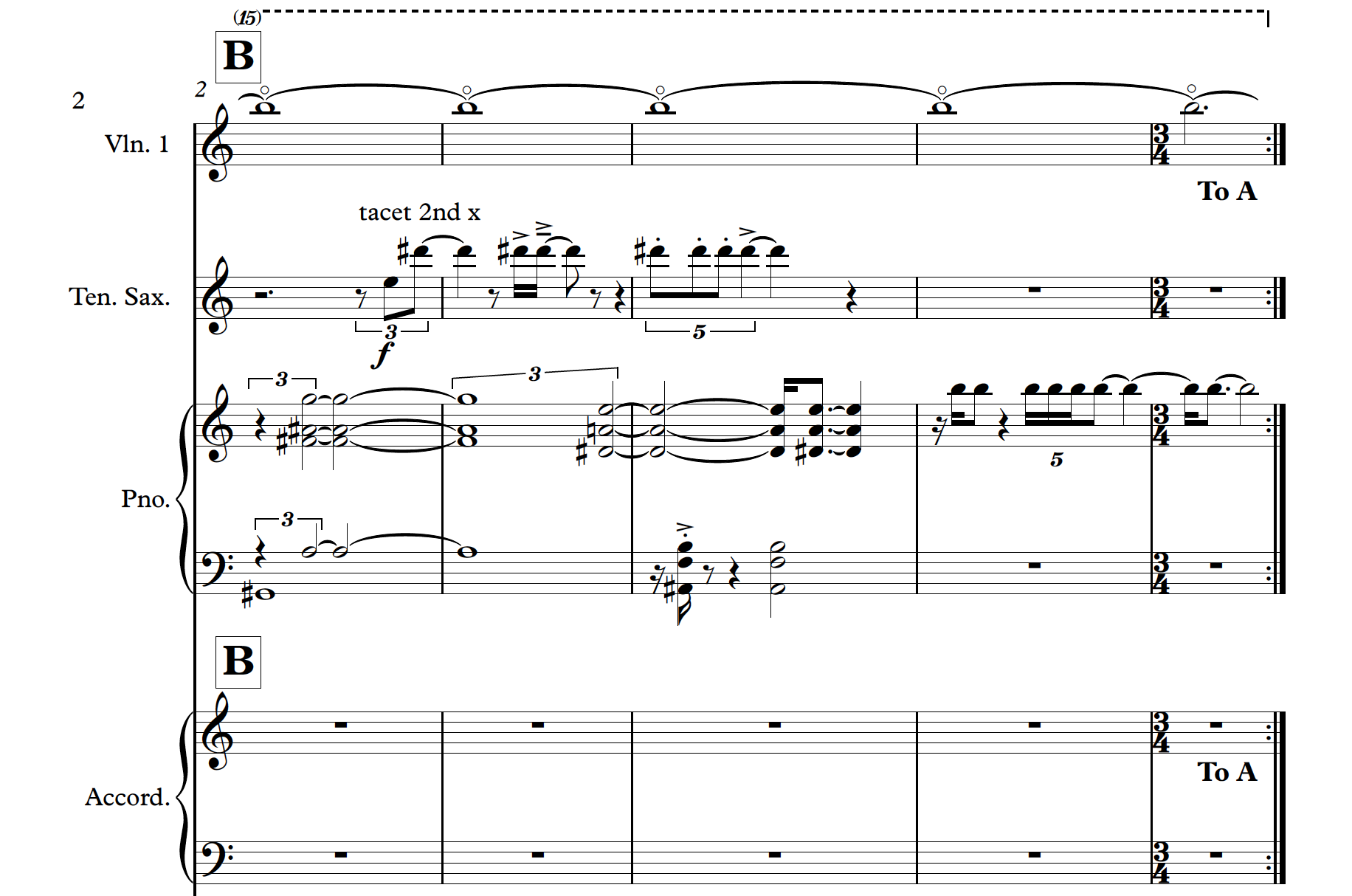

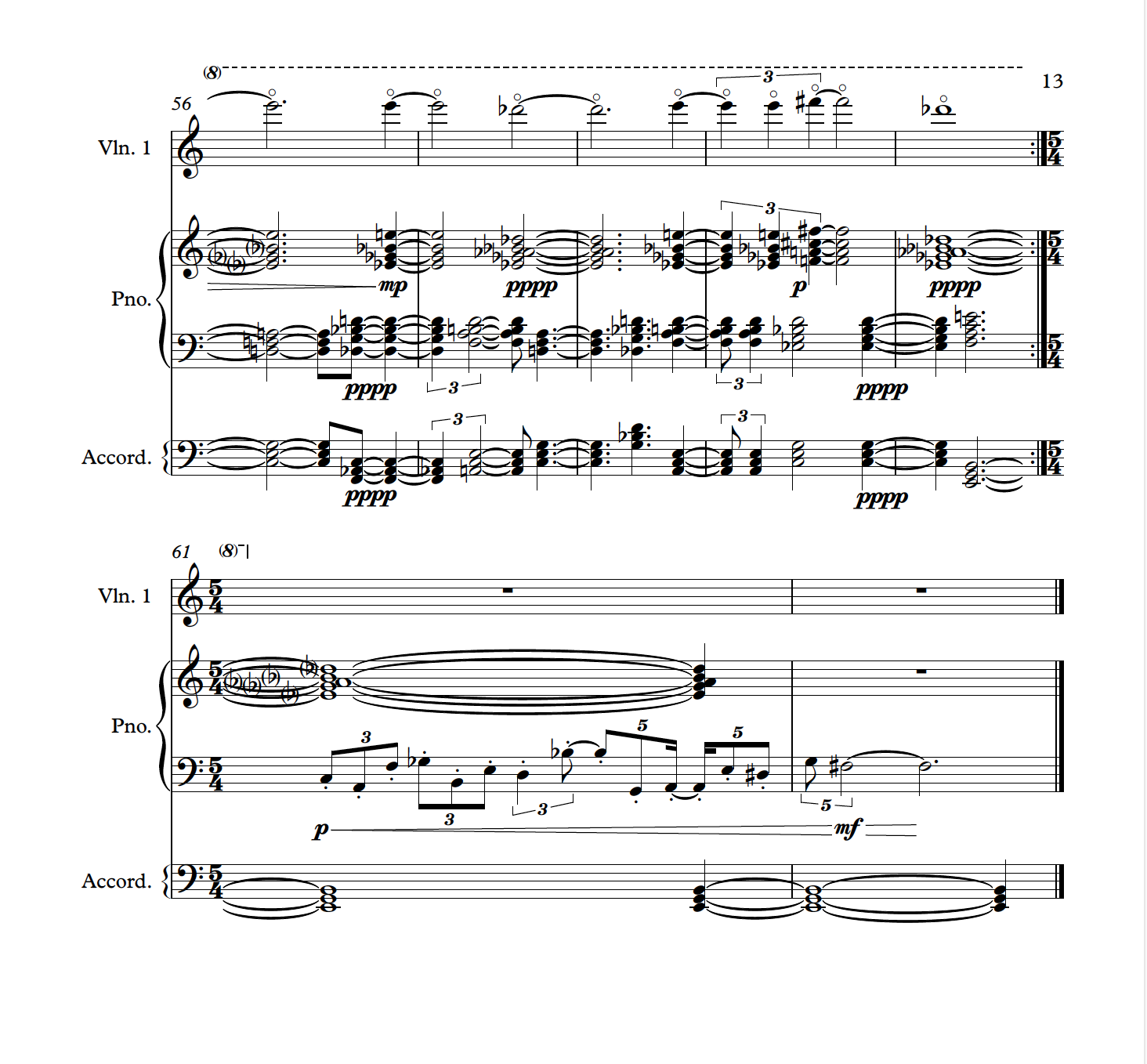

Although the players are free to improvise in whichever way they see fit, they have to snap back into their composed parts quickly. The allocated improvised sections tend to be very short, almost forcing the musicians to make brief, but clear musical statements. Time signatures vary and the tempo continues throughout, with the exceptions of the two A sections and measure 39, which is extended for a short full group improvisation. The saxophone and piano play a fanfare-like figure to separate the two A sections.

After the short group improvisation at C, the 4:3 figure is played in time as a musical cue to indicate that the tempo resumes. It is played by the saxophone the first time and by the accordion the second.

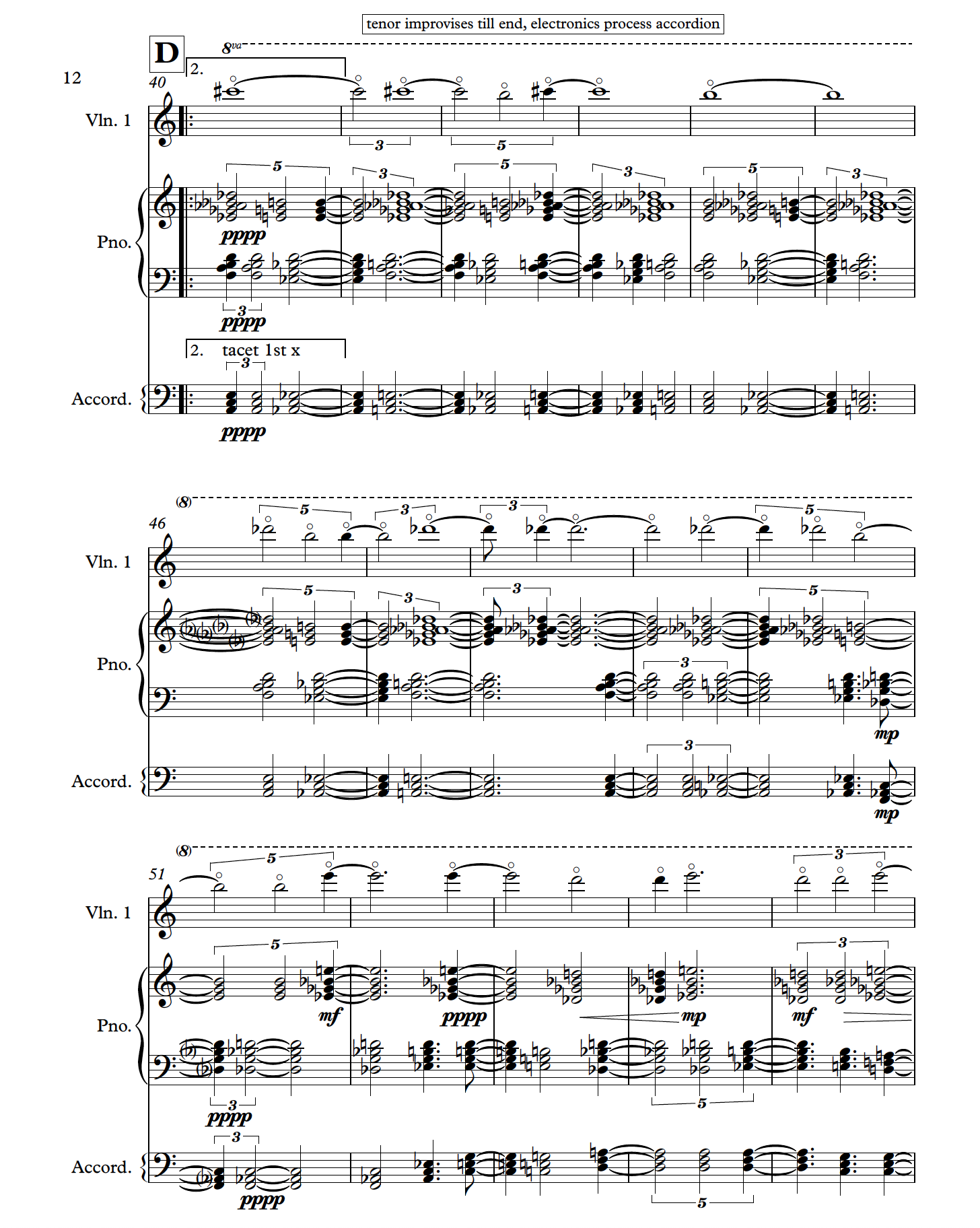

Section D is the only part of the composition where mutable and fixed roles are clearly defined over a long stretch of time. It's a twenty-measure-long loop, with one instrument added on each repeat, all as a backdrop for an extended tenor saxophone solo. The material played by the piano is an extension and expansion of the chords used in measure 35-39. The accordion plays in rhythmic unison with the left hand piano, but (mostly) using the triads below. This results in a murky texture, muddied even further by Sam's live processing. I wanted to create the effect of a tape that has been copied over and over, losing clarity over the course of time. It also generates a stark contrast for the last instrument to enter – the violin, doubling the top right hand piano, again with the high sul ponticello harmonics that are prevalent throughout the piece.

Circling back to Ellington, Mingus and the tradition of composing for specific musicians so prevalent in Jazz, brings me to why I chose the performers on this particular recording. One thing I realized is that the one person who connects all of us is the multi-reedist and boundary breaking composer Anthony Braxton. Anthony is possibly the living composer who has had the greatest influence on me, and a composer who has long incorporated musicians from different disciplines. I met Sam Pluta after I performed with Braxton, and Sam subsequently introduced me to the Wet Ink Ensemble. Adam Matlock, Zeena Parkins, and Cory Smythe also have all performed with Braxton, and Josh Modney recorded several of his challenging Ghost Trance Music compositions.

All of the players I asked to participate in my recording are extremely creative and have distinctive musical personalities and recognizable voices, but there is one other important aspect: they are all great composers in their own right. When players are given as much freedom as they are in my music, it helps to know that they have a sense for structure and architecture -- the macro “bird’s-eye view” I mentioned earlier. In an improvisational context what that means to me is not overstaying one’s welcome, making entrances count, generating ideas and reacting to others, but also — and perhaps most importantly — knowing when not to play.

What has perhaps become the most important part of making music with other people is a shared sense of passion, truth-seeking, friendship and mutual respect. If we want to live in a better world, we have to strive to become better people ourselves.